Researchers have reported a pattern of evolution in the teeth of the Sagebrush Vole, over the last approximately 1 million years, from three locations in North America. One in New Mexico, one in Colorado, and Kennewick Road Cut here in Washington.

My doctoral dissertation research is focused on studying the process by which evolution occurs. To understand evolutionary process, we must carefully investigate patterns of evolution and understand their contexts.

To understand broad contexts, paleontologists need to understand the temporal context of a locality. When material from KRC was originally described by Drs. John Rensberger and Anthony Barnosky in 1982, they used the presence of the Sagebrush Vole to infer how old material from KRC was, suggesting it was between 6,600 years old at the top of the locality and approximately 175,000 years old at the bottom.

The approach for identifying the age of fossil localities, based on the animals contained within them, is called biostratigraphy—an important field of study within paleontology. Unfortunately, since this original description of KRC, fossils of the Sagebrush Vole have been found in additional localities in North America that have been radiometrically dated to be older than the inferred dates for KRC (nearly 1 million years old, in fact).

We know that the material from KRC is at least 6,600 years old, because it is capped by a carbon-dated ashfall from a volcanic eruption. However, we don’t know how old the material underneath that ashfall is, which means we do not have the context needed to use the fossils from KRC to understand the evolution of animals in North America.

This is quite a shame, because there is a plethora of material from KRC and it represents one of the best-stratified deposits in North America. Therefore, in order to use the material from KRC to its fullest it is necessary for paleontologists to revisit the material collected from more than 30-years ago and assess it for fossils that may provide alternative dates via biostratigraphic inference.

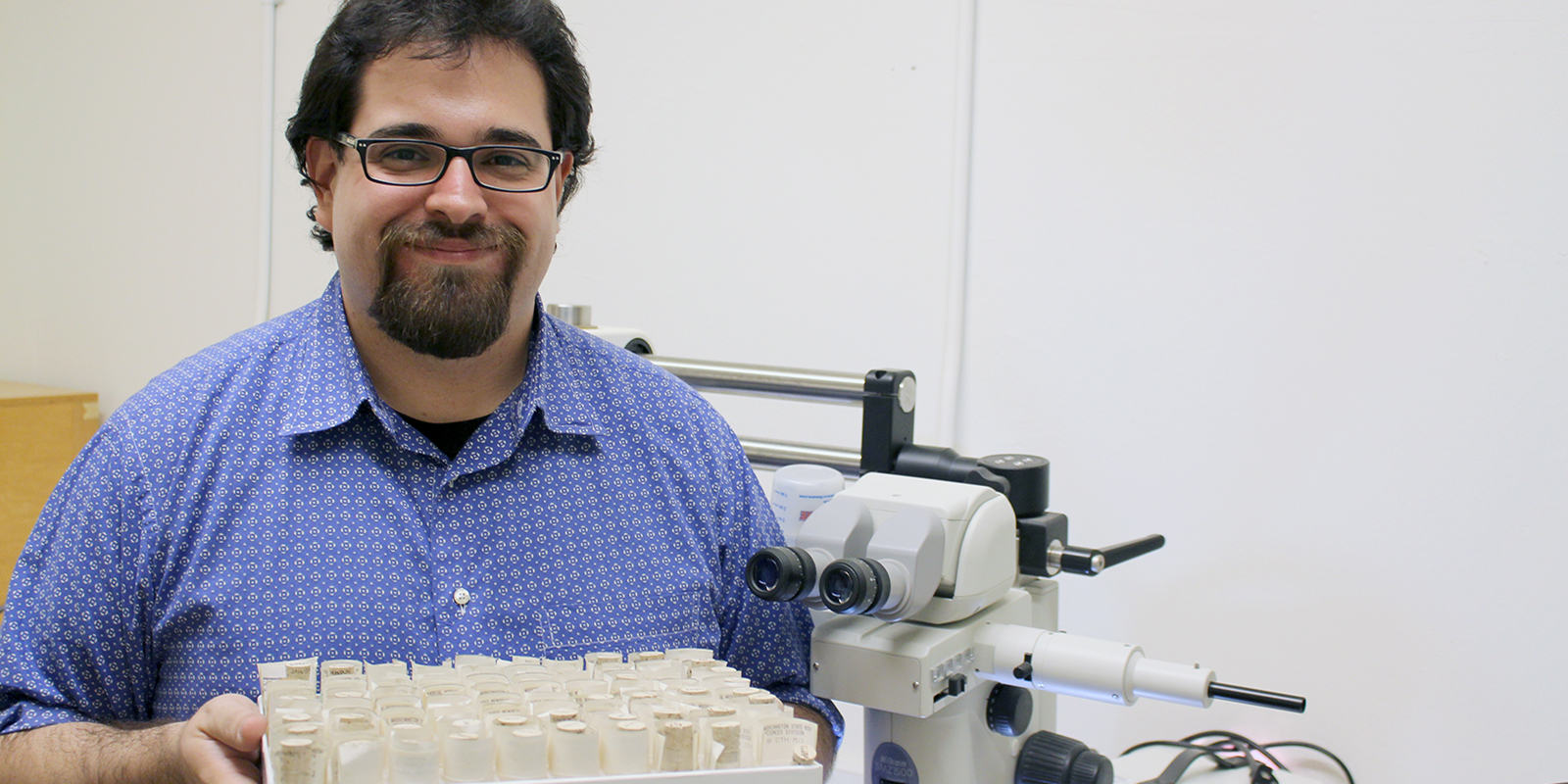

Fortunately for me, because of the care taken by the researchers who collected the material and the subsequent care by the curatorial staff at the Burke Museum, I am able to examine this material for precisely this purpose! This underscores the extreme importance of natural history museums like the Burke as archives of history.

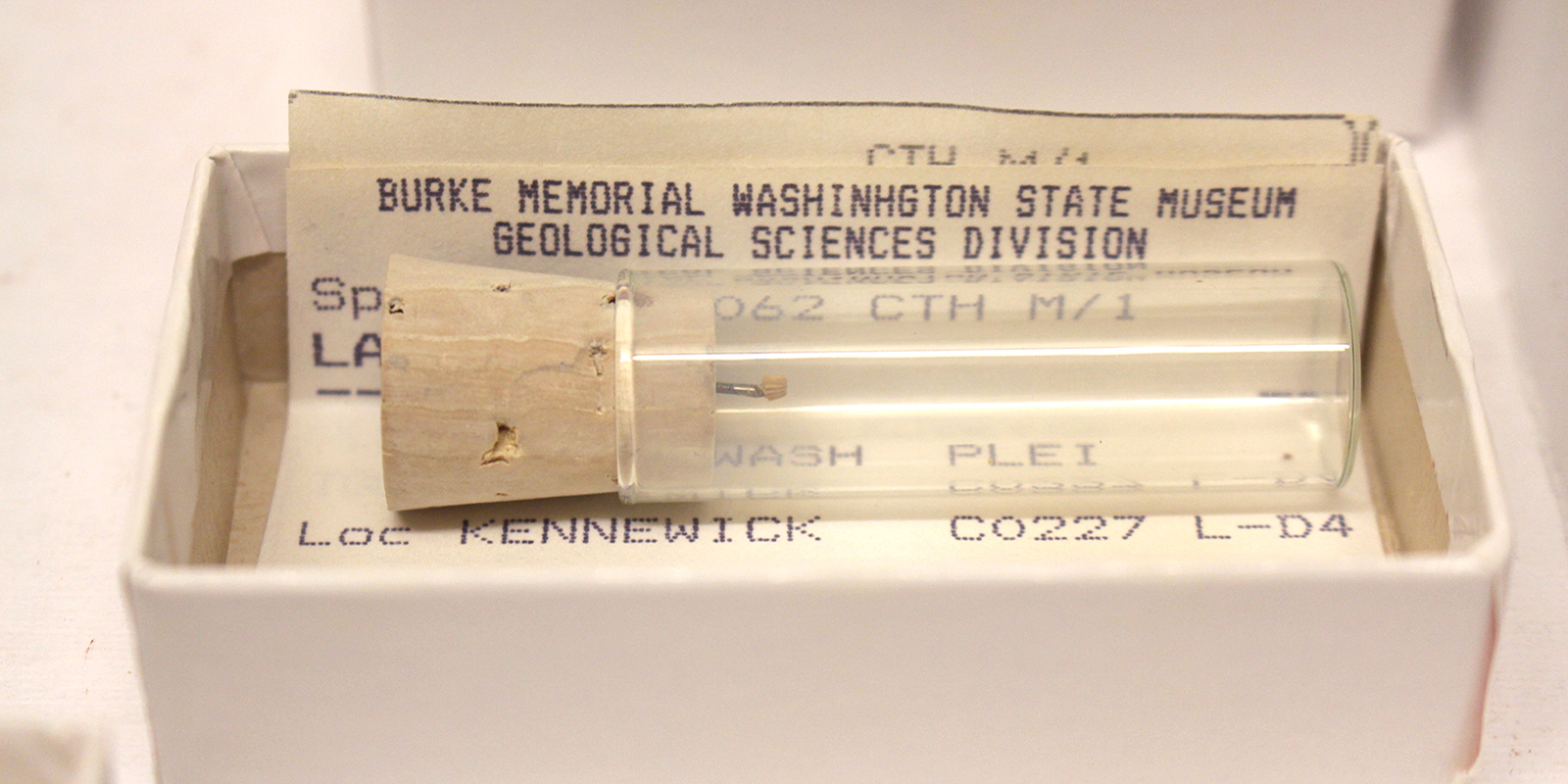

A Sagebrush Vole tooth in the Kennewick Road Cut collection.

Microfossil specimens in the collection.

___

Robert Burroughs is a PhD candidate at the University of Chicago with the Committee on Evolutionary Biology. To learn more about his research visit his website. See more fossils in the Vertebrate Paleontology collection or learn more about the Vertebrate Paleontology Collection study grant.