What are you studying?

My research focuses on using our knowledge of the evolutionary relationships between species to help understand evolutionary patterns over really long periods of time, up to tens of millions of years.

What are you working on right now?

At the moment, I'm working on North American terrestrial mammals from two periods of time called the Arikareean and Hemingfordian that lasted from about 30 to 15 million years ago.

Why focus on these periods of time?

These periods of time are interesting because North America was separate from South America but occasionally became connected to Asia via a land bridge when sea level was low. We call the area that forms the land bridge Beringia; it lies between what is now Alaska and eastern Russia. Each time sea level became low enough to expose the land bridge many species would travel across, invading North America from Asia, and vice versa.

What do you hope to learn?

I’m interested in finding out what effects these big migrations of many species had. From looking at invasive species in the modern day we know that sometimes they can be very successful and make it difficult for the endemic species (those that already live in an area) to survive. However, we don't know as much about how the endemic species might evolve in response to competition with invasive species, or how the invasive species might evolve, especially in the long term.

Any reason why carnivores in particular?

Carnivores are a good group to use to start to answer this question because we know several carnivore species made the journey across the land bridge into North America, and they have been very well studied so we know a lot about what species there were and how they were all related to one another.

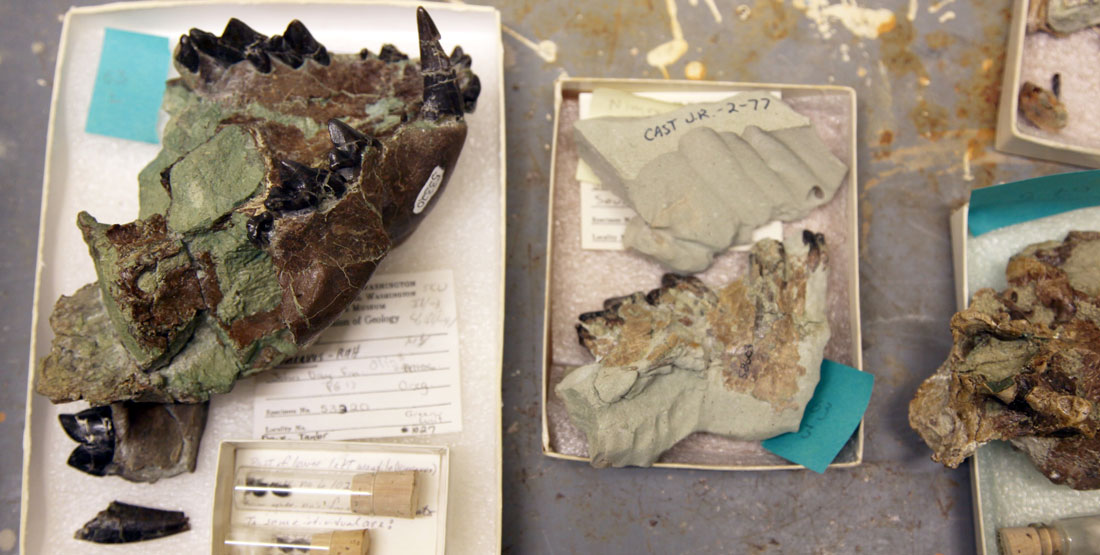

Carnivore fossils in the Burke Museum paleontology collection.

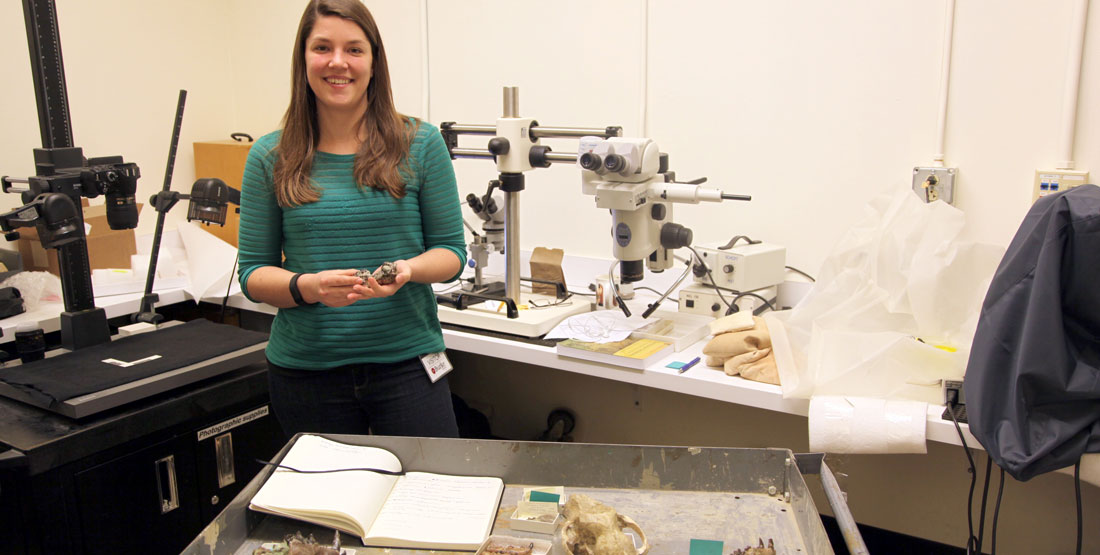

Each specimen is photographed and measured.

How are you doing this research?

I’m using a mathematical model that describes how we would expect species to evolve over time under different circumstances. For example, how they would evolve while the climate and vegetation are changing or while they are competing for resources with other species. When looking at fossils information can be missing; a lot of the time we only find the teeth of ancient mammals, because these are the part most likely to be preserved. In addition, there may have been other species around that we haven’t found a fossil of yet, or others that never fossilized in the first place. The model I use also takes this missing information into account to show what patterns of evolutionary change we should expect to see. I can then make measurements of real fossils and compare this to the pattern predicted by the model, to find out which type of model best fits to the real data.

What brought you to the Burke?

I've come to the Burke museum to collect that real data—to look at and take measurements of fossil carnivores. There are several good areas in the Northwest to find fossil mammals from the period of time that I’m interested in. This means a lot of those fossils are now stored at the Burke Museum, so it’s a great place for me to come to see lots of good carnivore specimens.

Laura Soul researching in the Burke Museum paleontology collection.

A selection of carnivore fossils in the Burke Museum paleontology collection.

A special thanks to Laura Soul for sharing her work with us!

Laura Soul is a Peter Buck Deep-Time postdoctoral fellow in the Department of Paleobiology, Smithsonian Institution National Museum of Natural History. See more fossils in the Vertebrate Paleontology collection or learn more about the Vertebrate Paleontology Collection study grant.