Columbian Mammoth by Gabriel Ugueto.

A Columbia Mammoth fossil in the Burke Museum's Fossils Uncovered gallery.

“Science and art are a lot more closely linked than people think,” said Gabriel Ugueto, a paleoartist and former herpetologist who created several illustrations used in the new Burke Museum. “Paleontology needs artists to show their hypothesis to the public, to recreate what their findings are. Even a mammoth skeleton, it doesn’t translate the same as when you put flesh and bone and show people what these animals would have been doing when they were alive.”

Seeing a mammoth skeleton is awe-inspiring (we’re pretty fond of our Columbian Mammoth) but seeing an illustration of that mammoth covered in fur, foraging for food during the frigid cold of an Ice Age helps to tell a larger story about that species’ life history. In the Burke Museum’s Fossils Uncovered gallery, fossils and paleoart are paired to show how that plant or animal would have looked and how it would have interacted with its environment.

“These paleoartists did some incredible work for the Burke Museum,” said paleontology curator Dr. Christian Sidor. “Their life restorations are critical bridge between paleontologists and the public.”

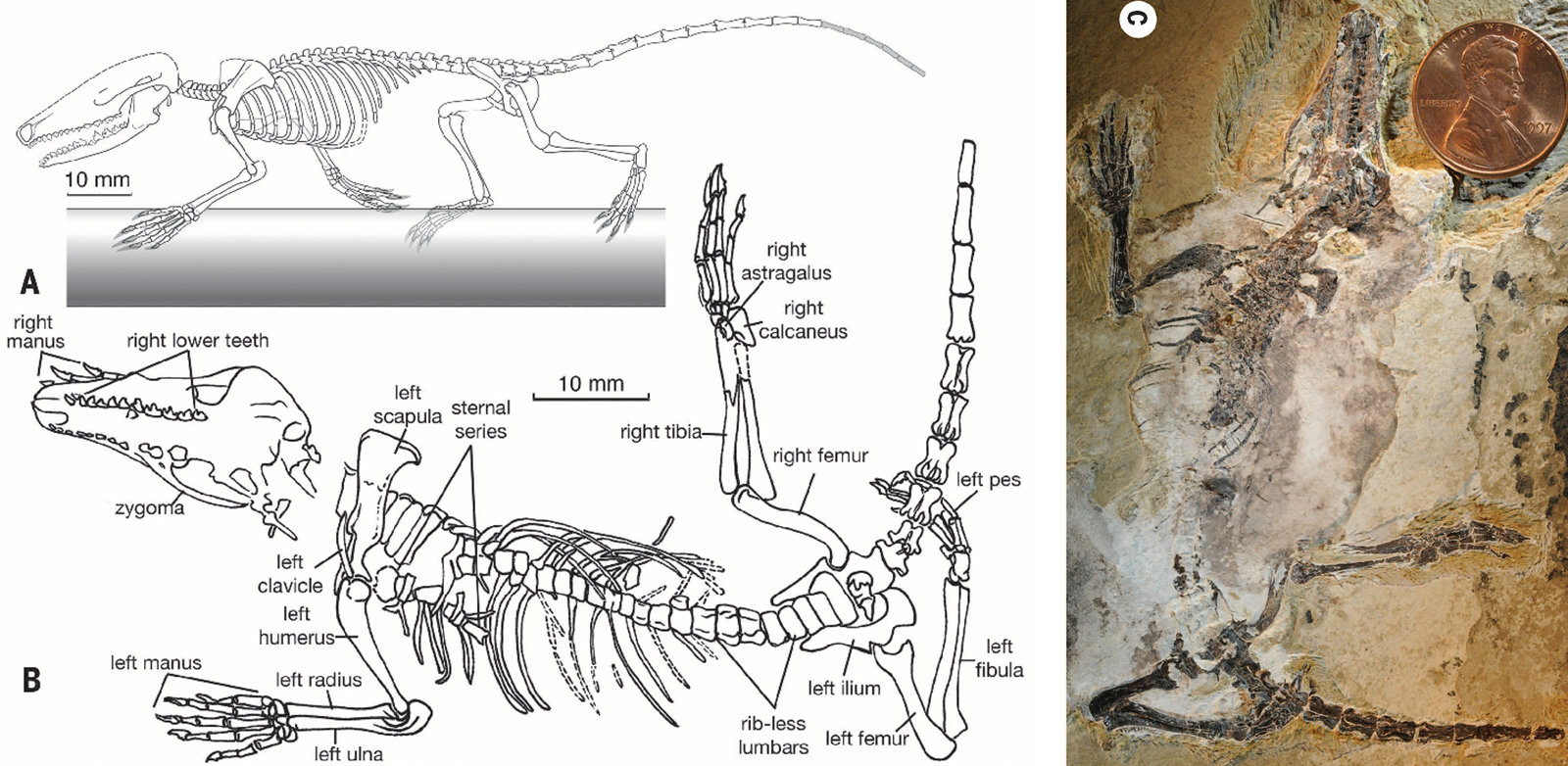

To depict extinct animals accurately, especially ones that don’t have as similar a modern day relative as the mammoth, it helps to have a strong understanding of anatomy and biology. It gives the artist a better sense of how muscles and soft tissue would attach to the fossilized bones left behind and what modern day species might have similar characteristics.

“A big part of being a paleoartist is to read a lot,” Ugueto said. “I try to get as much information and read as many papers as I can on the species that I’m going to depict. What studies have been done? What’s the morphology like? What do we know of the habitat that is probably lived in? What was the temperature and climate at that time and place?”

Seeing the fossils in person is one of the best ways artists can get a sense of what the animal will look like, but they must also use the scientific literature and inferences based on the environmental conditions that the species lived to fill in gaps in the fossil record. Learning the basic details of the animal—what it ate, how it avoided predators, where did it live, what was the climate like back then—can help artists pinpoint what makes this species unique in the fossil record.

It’s becoming much more common for paleoartists to rely on 3D scans of fossil specimens, especially when access to the fossils is difficult. These 3D models allow artists to see the fossil from every angle, so if they’re trying to figure out exactly how the head would look in their illustration, they can just rotate the model until it matches.

Burke Museum volunteers are working hard to 3D scan fossils in the collection to increase access for the public and paleoartists alike. But even with pictures and 3D scans at their disposal, paleoartists have to ask the experts for help sometimes because who knows these extinct species better than a paleontologist?

“Paleontology is an ever-changing field and fossil bones can only tell us so much, so it's important to keep in contact with the community to be aware of new discoveries and the latest supported theories,” said Julio Lacerda, a paleoartist based in Brazil who worked on several illustrations for the new Burke.

Paleoart, like the research it depicts, is constantly evolving as new information comes to light, so if new evidence is found that an extinct whale had baleen and not teeth, then the illustrations must evolve to reflect that.

Some of the more famous depictions of dinosaurs come from movies like Jurassic Park where animals are constantly hunting or fighting, but other paleoartists rarely depict animals in scenes of violence. Instead of drawing Hollywood-style ferocious dinosaurs, they show them doing what animals actually spend most of their time doing: eating, moving around, mating, or even sleeping.

“I like to depict them doing things like sleeping; you don’t see it that often but it’s what animals are doing most of the day,” Ugueto said. “I always try to convey that these animals weren’t movie monsters, they were just animals. It’s important to show people how familiar and unfamiliar these species are.”

These illustrations show us how these long-extinct animals aren’t all that different from the species that live on earth today. Some may have long necks, or sharp teeth, or just be overall bigger than anything alive today, but they still lived much like species today.

If you want to try your hand at paleoart, all you need is something to draw with and a passion for paleontology. Come stop by the Fossils Uncovered gallery to see dozens of amazing examples of paleoart right alongside the fossils that inspired them.

Thank you so much to Gabriel Ugueto and Julio Lacerda for being a part of this article and creating such beautiful illustrations for the Burke Museum. You can find more of their work at the links below:

Gabriel Ugueto

Website: https://gabrielugueto.com/

Twitter: @Serpenillus

Julio Lacerda

Website: https://paleoart.tumblr.com/

Twitter: @JulioTheArtist