The Journey of the Burke Museum’s Land Acknowledgement

At the Burke Museum, we are on our own journey to authenticate our relationship with tribal communities, people we work with, collections, and future research opportunities. To have a land acknowledgement is to change the narrative for the communities we work with and with the collections we care for.

In our own path to get a land acknowledgement, we embraced tribal consultation. As a state museum collaborating with sovereign Tribal nations, this work is done through government-to-government relations that breaks down the western-centered relationship or academic approach to the traditional work of a museum whose authority predominately lives with non-Native curators. The Burke’s Native American Advisory Board (NAAB) was instrumental in guiding the land acknowledgement, with NAAB members comprised of tribal leaders and cultural knowledge keepers from across Washington state. Our end goal is to create a safe place for tribal communities and individuals to come and reclaim their science, stories, and technologies through the collections that are held in the museum. The land acknowledgement is one part of this greater goal.

Tribal elders and leaders are the experts and knowledge-bearers who generously shared their perspectives and guidance with the Burke. Through this consultation, we co-created the Burke’s land acknowledgement:

“We stand on the lands of the Coast Salish peoples, whose ancestors have resided here since Time Immemorial. Many Indigenous peoples thrive in this place—alive and strong.”

The Burke went through several iterations around naming which tribes are in the land acknowledgement, knowing that we hold the collections of so many Indigenous communities and tribe’s ancestors and belongings from across the globe.

This is a living statement—not just a written statement—that will change over the years as the relationships and collaboration with Indigenous communities grow and change. Our intent is to show where the Burke stands is a place that is now also a place of cultural safety.

Creating Your Own Land Acknowledgement

First and foremost, we ask that other organizations do not copy the museum’s land acknowledgement as your own. It is humbling to have others reach out for advice. However, at the Burke, we are on our own journey. We have much to continue to learn.

I encourage you to take on this deeply important work in a way that is authentic and meaningful to your organization, and done in consultation with tribes and Indigenous communities.

Setting your Intention

While land acknowledgements are an important way to recognize the Indigenous peoples who have resided on the lands you’re on since Time Immemorial, the intent behind—and how you develop a land acknowledgement—are as important as the words themselves.

If you would like to develop one, take time to reflect and ask yourself some important questions that will guide you in doing the work in a thoughtful, meaningful way. Ask yourself questions like:

- Why now? Why are you creating a land acknowledgement at this time?

- Are you doing this to check a box?

- Are you doing this because of the social justice issues going on and this your attempt to figure out how to move forward in having conversations about colonial harm? Has your organization itself been a part of the harm?

- What is your relationship with the original stewards (tribes, bands, Indigenous peoples) of the lands you stand on?

- What process of reconciliation has your organization done to address the displacement of Native peoples?

Land acknowledgements are also a way to change the narrative of the history and break down the unconscious bias through the historical context and education we’ve had through our Western educational system.

With this lens, additional questions to consider are:

- Are you leading this to break down the stereotypical biases of Native peoples?

- Are you willing to bring Tribes to the table?

- What is your end goal and the type of impact you’re making to your audience?

The concept of whose land you are on is complicated. It is a part of the colonial legacy of the United States and many other countries. Indigenous peoples historically didn’t have the boundaries that were enforced on them through reservations and the forceful removal from their ancestral lands. Many tribes and Indigenous peoples often shared the same lands and territories. It is important to consult with as many local tribes as possible, and not assume today’s boundaries reflect the ancestral territories that once stood.

If you are interested in developing your own land acknowledgement, we recommend the Native Government Center’s (NGC) guide to Indigenous Land Acknowledgement. Among other recommendations, the NGC encourages land acknowledgements to not be grim, use language that is empowering to Indigenous peoples, and upholds the people and cultures that are still present today.

Looking to the Future

Doing this work regarding land acknowledgement also is for our Indigenous youth, for future generations so our kids know who they are. We have a lot of people disconnected through our culture and reclamations, stewardship, and acknowledgement helps our youth understand who they are and where they come from. It’s all about empowering the next generation.

Land acknowledgements also help non-Native staff and visitors learn about the diversity and thriving cultures of Native peoples. By hearing whose lands you’re on at the Burke, it can help everyone learn who is here and hopefully start to think of land and ownership in a different way. And afterward, take this perspective with you to other places and think about whose lands you’re on and the Indigenous peoples that have always been there.

Recommendations for how to Implement a Land Acknowledgement

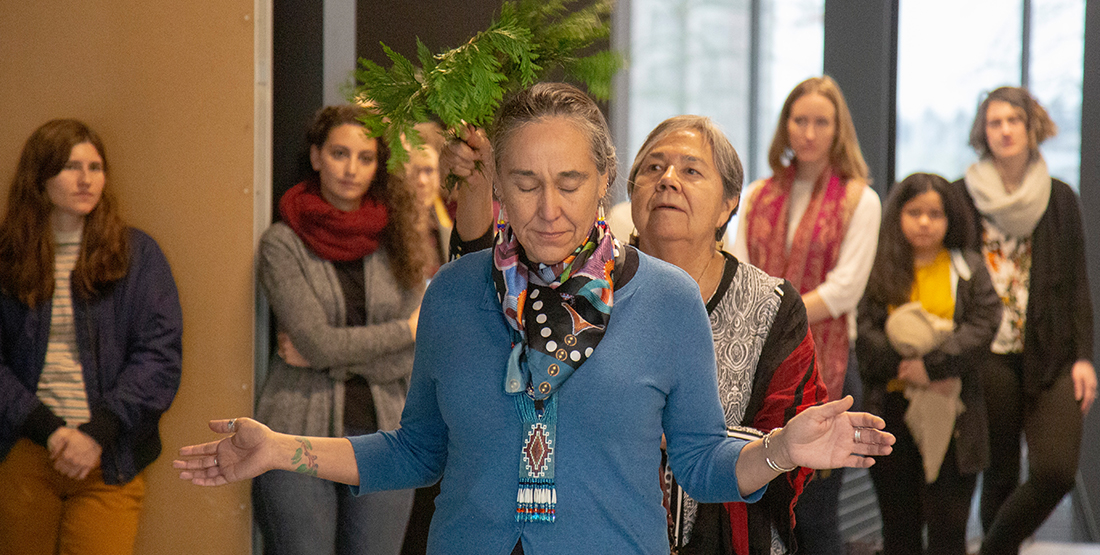

We caution others to avoid the romanticized and performative approach of asking a Native elder to come bless the land and do the land acknowledgement. This can perpetuate the stereotyping of Indigenous peoples as part of past communities and spiritualizing the relationship to the land.

At the Burke, we each take turns speaking our land acknowledgement at the beginning of each meeting or gathering. A Burke team member volunteers to provide the land acknowledgement, and what that means to them personally that day. For the Burke’s practice, it allows the individual to build a relationship with the land. It engages us all in the practice—to change, to unlearn, and to recognize and acknowledge biases.

Additional Resources

Native Governance Center’s Guide to Indigenous Land Acknowledgements

Land Acknowledgements are about Better Relations, not just Checking a Box. By Ta7talíya Nahanee, published in IndigiNews on February 18, 2021.