But it is an important part of the “behind-the-scenes” process of a natural history museum to document and preserve life around us—adding to the library of biodiversity that is used by researchers and the public alike.

Specimen preparation can take several forms depending on the type of animal. For birds and many mammals, the process involves removing all of the bones and innards of the specimen and creating an archival “study skin” by stuffing the skin with cotton. The bones are saved and paired with the study skin. In other cases, such as with marine mammals, only the skeleton is preserved. Other specimens, like fish, amphibians and reptiles, are often preserved in jars of ethanol.

The vast majority of specimens that are added to the Burke collection also have a DNA tissue sample removed and added to the genetic resources collection—one of the largest of its kind in the world.

How does the Burke acquire these specimens? Many are found dead and are then collected by trained citizens or Burke staff along with relevant data. Some are confiscated from U.S. Fish & Wildlife and other organizations. And some animals are collected by scientific researchers in an effort to document the biodiversity of a region.

All of the specimens are available to researchers and the public to answer the questions of today—but more importantly they’re in the collection forever and will be a resource to answer questions that haven’t even been asked yet.

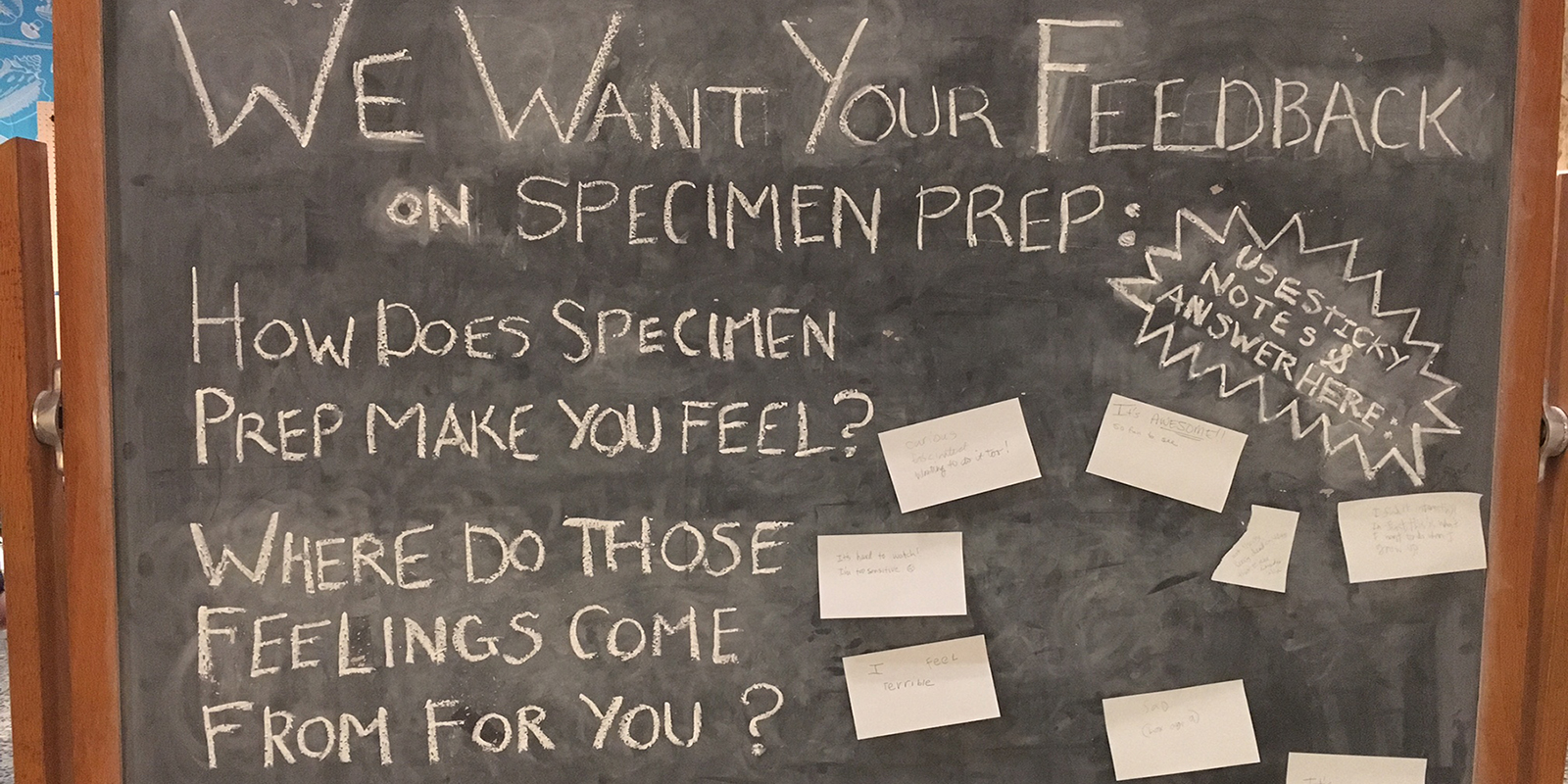

In the Burke’s Testing, Testing 1-2-3 exhibit, prototyping the “inside out” museum experience of the New Burke (opening in 2019), visitors could observe museum staff and volunteers carefully preparing birds and small mammals on the other side of a glass window.

Though this process can appear graphic to some people, we set out to learn how visitors would respond to one aspect of what happens behind the scenes of a natural history museum. Overall, the visible specimen prep received a tremendous amount of positive responses from visitors and staff alike!

We asked ornithology student researcher Cooper French and collections interpreter Aletheia Wittman to describe their experiences with introducing the public to specimen preparation.

Cooper French, Ornithology student researcher

Working in Testing, Testing, 1-2-3 was a fascinating experience for me, because it reminded me of the visceral and emotional nature of specimen preparation. I've been preparing study skins for the Burke and other museums for a little over four years now. As a result, I’ve progressively lost the sense of wonder and disgust in the process.

Specimen prep is roughly equal parts science and art, coupling avian anatomy with the tactile skills of cutting, peeling, sewing, and preening. I've prepared in the labs at the Burke and in the field, in weather that ranged from 100-degree heat to a freezing snowstorm.

Seeing visitors react to the work I was doing was a great reminder of how unusual this process is. The emotions ranged from fascination (two young boys stood watching for so long they eventually dragged stools over so they could sit and gaze), to shock, to complete indifference.

Holding up the wing of a California Condor to show a family the size of the bird and the pattern of molting feathers along the edge pulled me out of my routine and rekindled the sense of wonder in what I was doing. I was touching an animal that few people ever get to see, preserving some distilled element of it into a specimen that would be curated for hundreds of years. That Condor wing, with that molt and those colors, would likely outlive me.

Like all of the specimens I prepared in Testing, Testing 1-2-3 this summer, that wing is a part of a body of scientific knowledge that the Burke produces and protects. It was a joy for me to not only share what I was doing with the public, but to gain perspective on my role within the museum and the greater scientific community.

Alethia Wittman, Collections Interpreter

The Burke's Interpretation staff and volunteers were ready to answer any visitor’s questions or concerns about animal prep. Visitors frequently asked questions about the specifics of the preparation process. They also commented on how professional and caring the process appeared; comforted to see this process in such good hands. Adults were eager to share the scientific process in action with children who were interested in biology, saying "Look! This is what scientists do! Would you want to do that?" Often children and young people responded with interest and curiosity.

Gallery observations conducted by external evaluators in the exhibit revealed that, when an animal prep researcher was working, 69% of observed visitors chose to linger or intentionally watch the prep process. We also know through data collected from our in-gallery visitor poll that the majority of visitors had positive associations with seeing animal prep happening in Testing, Testing 1-2-3. I talked with many of these visitors who watched, transfixed as Cooper, Katie, Jeff and the rest of the team carefully went through the stages of preparing shrews, bats and birds of all kinds.

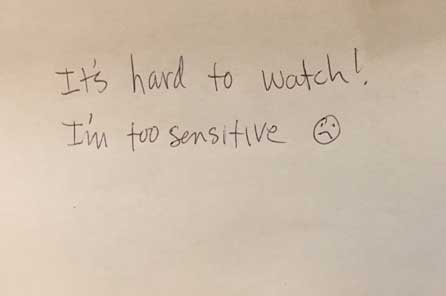

Not everyone was excited to see animal prep, however. Many of the visitors who shared their strong negative reactions with me were children. Children were very forthright in their responses of "Ewww!" or "You killed it!" or, memorably for me, a silent tear rolling down the face of a very young boy as he peered into the window of the prep lab.

And it wasn't just children that had visceral responses. Some visitors felt conflicted when they saw animal prep, saying they felt sick to their stomachs, but were simultaneously fascinated and thought it was valuable work. To these responses, I and volunteer interpreters would always seek to engage with them, acknowledge their feelings and reactions, and share more about the context for a process that most visitors were seeing for the first time.

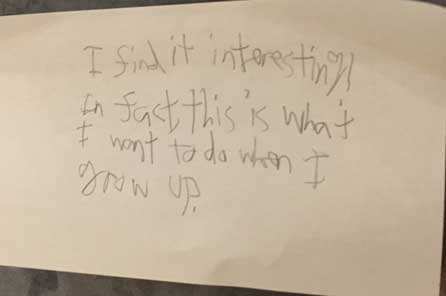

Visitor feedback about the specimen prep: "I find it interesting. In fact, this is what I want to do when I grow up."

Visitor feedback about the specimen prep: "It's hard to watch! I'm too sensitive."

The inside-out experience of Testing, Testing 1-2-3 offers an opportunity to dialogue with visitors about their real-time responses to Collections processes like animal prep. These conversations generated new entry points for visitors to connect with the Burke's collections, and simultaneously expanded my own understanding of how we should shape our approach when in dialogue with visitors.

We’re applying visitor and staff feedback gathered during this experience directly to how we’ll approach interpreting the process of animal preparation in the New Burke Museum when it opens in 2019.

---

Learn more about Testing, Testing, 1-2-3 and the New Burke.