Photo: Burke Museum

A humble blanket with a rich history

The blanket bears a simple design, and its origin remains somewhat of a mystery.

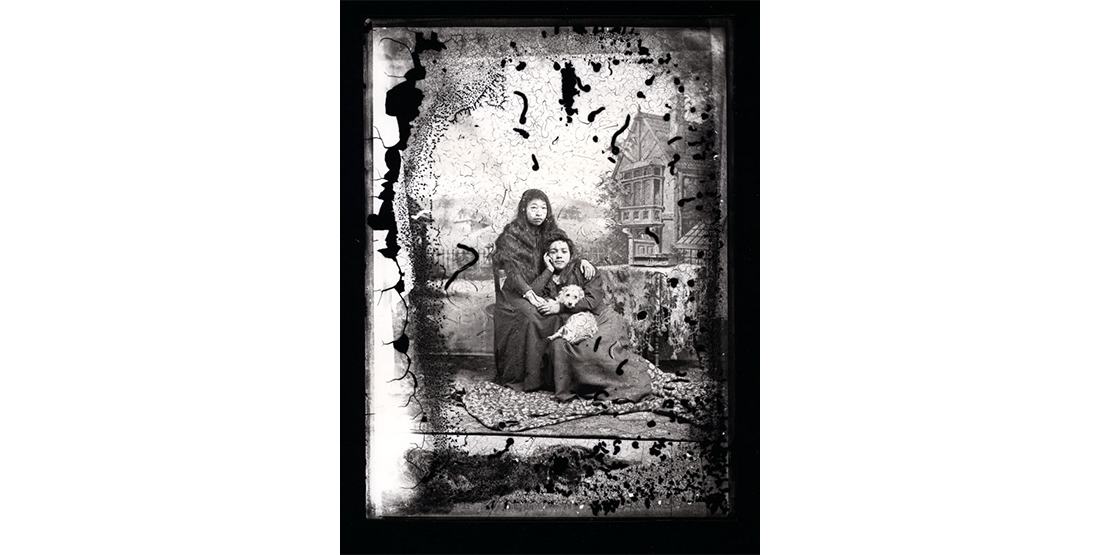

Records describe the blanket only as “Coast Salish” and unfortunately do not include information on the original Salish creators or owners. It was owned by Judge James Wickersham, a collector of Northwest Native objects who lived in Tacoma, Washington, from 1883–1900, then moved to Alaska. After his death in 1939, Wickersham’s collection was sold to a tourist store in Alaska, where a collector recognized the authenticity of the objects. They were donated to the Burke Museum in 1974.

The blanket may have remained obscure were it not for a tear that reveals its incredible craftsmanship. It is a plain weave (or tabby weave) blanket—meaning that a single weft thread was woven over and under the warp threads without crossing.

Photo: Burke Museum

“As soon as I saw the warp yarns exposed within the tear, I knew this was an unusual blanket,” said Liz Hammond-Kaarremaa, a Coast Salish spinning expert. Hammond-Kaarremaa received a grant through the Museum’s Bill Holm Center to study Coast Salish blankets and robes in the Burke collection.

The unusual warp in this blanket is made from a combination of string, bark and sinew. As she pored over the blanket, she began to suspect the materials used to weave it may also have included woolly dog hair. "The warp caught my attention but it was the weft that posed the mystery: the weft fiber did not look like mountain goat, nor did it look like sheep wool. It looked like woolly dog hair I had seen at the Smithsonian.”

Little dogs play a big role

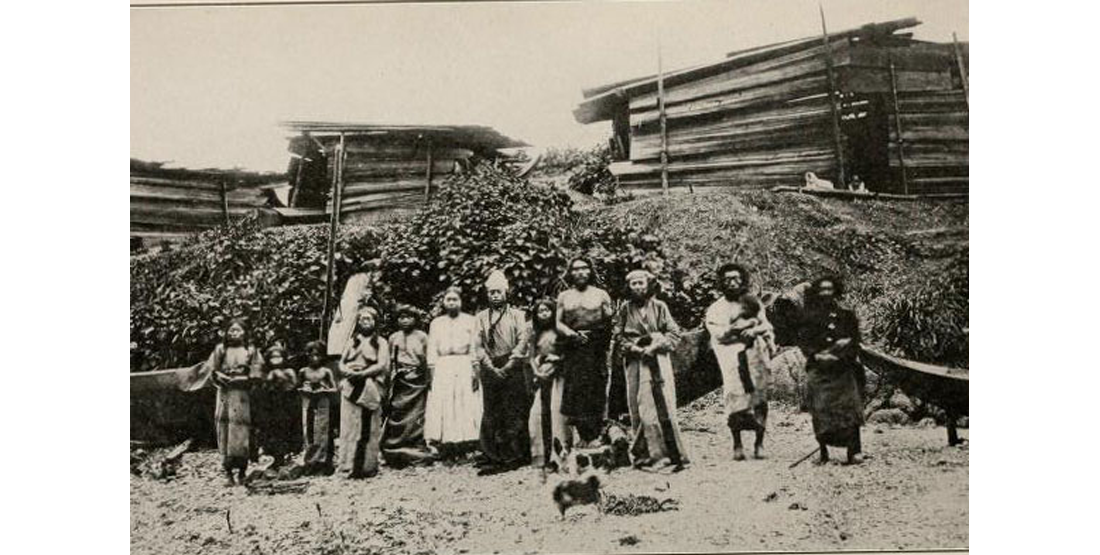

Raising dogs to use their hair in textile production was a sophisticated practice unique to the first peoples of the Northwest. Woolly dogs were distinct from other dogs kept by Coast Salish peoples, and were often kept in corrals or even on their own small islands to keep them from interbreeding with hunting dogs, since their long woolly hair was a recessive genetic trait. They were small and spitz-tailed, with straight ears and thick long hair.

Capt. George Vancouver made the first written observations of the woolly dogs in 1792 while anchored near Restoration Point at the south end of Bainbridge Island, just across from what is now downtown Seattle. He described them as “all shorn as close to the skin as sheep” with hair that could be “lifted up by the corner without causing any separation” and was “capable of being spun into yarn.”

Woolly dogs were an important part of Coast Salish life for more than 1,000 years, but they were extinct less than 150 years after the first European explorers landed on the Northwest Coast. The dogs interbred as Hudson’s Bay Company and other more easily acquired blankets became available. In addition, introduced diseases in the 18th and 19th century devastated communities and disrupted many cultural practices, including the breeding and husbandry of woolly dogs.

While weaving with woolly dogs is part of Coast Salish oral traditions and documented in early explorers’ journals, the dogs and the important role they played were lost from popular history—and objects made from their hair were lost, destroyed or disappeared into museum collections.

As soon as I saw the warp yarns exposed within the tear,

I knew this was an unusual blanket.

Liz Hammond-Kaarremaa

Photo: Burke Museum

Photo: Burke Museum

Research and revival

Researchers began using technology to look for the presence of woolly dog hair in Coast Salish textiles from the 19th century. In 2011, a study led by Dr. Caroline Solazzo from the University of York used proteomics to discover dog hair in seven objects from the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History and the National Museum of the American Indian, some of which were collected on the Lewis and Clark expedition.

Advanced microscope analysis of the Burke’s blanket was conducted by Elaine Humphrey and Terrence Loychuk, at the University of Victoria Advanced Microscopy Facility, who have used light and scanning electron microscopy techniques to investigate the materials used in several Coast Salish blankets.

The Burke’s blanket is the only object in a Northwest museum confirmed to be made with woolly dog hair. It will be a critical resource to Coast Salish weavers, who study objects in museum collections to revive complex techniques and better understand the unique materials used in traditional textiles.

“This exciting discovery brings attention to a fascinating piece of Northwest history, and connects the Burke’s collections to this unique, Coast Salish tradition,” said Dr. Kathryn Bunn-Marcuse, Burke Museum curator of Northwest Native art. “We look forward to sharing the blanket with weavers and other researchers, so that it can be reconnected to the Indigenous knowledge systems from which it came.”