How long have you been involved with the Burke, and/or what did you do before coming here?

I joined the University of Washington as an assistant professor of Anthropology in 2013 and in 2015 I became an adjunct curator in Burke archaeology as I regularly integrate the Burke collections into my seminar and lab courses. In 2020 I was officially appointed as a curator of archaeology.

What’s excites you as you step into this new role leading the Burke Museum during this transition period?

When I first joined the Burke in 2020 I was thrilled to become part of a museum with such a deep commitment to showing how the histories and stories embedded in our collections are alive and present today. When I tell people I am an archaeologist they often think I deal with things that are long gone or decayed. But the real work of archaeology is about connecting past and present and understanding how what has come before remains present today. Really, this is also the work of a museum like the Burke. The collections we care for are part of living traditions and contemporary communities remain connected to them. And our museum and its staff work with these communities today — from local Tribal Nations to Indigenous and other affiliated communities across our region and around the world — to put back into practice the knowledge embedded in these collections.

I remain as firmly committed to this work as I have been throughout my career as an archaeology faculty member and curator and in this next phase I look forward to maintaining and strengthening the relationships the Burke has fostered with local Tribes in addition to myriad other local, regional, national, and even global communities who remain connected to our collections.

"When I tell people I am an archaeologist they often think I deal with things that are long gone or decayed.

But the real work of archaeology is about connecting past and present and understanding how what has come before remains present today."

-inline-400x600.jpg)

How do you typically approach your work and research? What can you share about your methods?

My research and work as an archaeologist examines the challenges and opportunities for creating Indigenous archaeologies. These are approaches to studying, caring for, and representing Indigenous heritage that are conducted with, by, and for Indigenous communities and Tribal Nations. Indigenous archaeologies — at their core — are expressions of the sovereignty of Tribal Nations to determine how their heritage will be cared for, now and in the future. What does this look like in practice? Since 2014 I have worked in community-based partnership with the Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde Community of Oregon’s Historic Preservation Office to define a way for using archaeology in its historic preservation efforts. As part of our work together we have defined what our team, Field Methods in Indigenous Archaeology, calls a Grand Ronde way for doing archaeology that uses tribal protocols and cultural values surrounding heritage. As part of this approach, we have developed a low-impact archaeological methodology which minimizes physical disturbance of ancestral places while ensuring Tribal heritage managers have information they need to best care for these places.

Many of the methods we employ are increasingly common in academic archaeology and especially so in work undertaken by tribal archaeology programs. They include geophysical survey instruments such as ground penetrating radar — which helps us see down through the ground to identify parts of sites not visible from the surface — and drone and aerial photography. But it would be a mistake here to only envision how such minimally or non-invasive methods may facilitate collaboration with Tribal Nations, without also considering how such collaboration contributes to the further refinement of these methods in the field. In my experience as co-director of three community-based research projects across California and the Pacific Northwest, collaborative thinking with Tribal heritage managers results in creative and rigorous assessments of archaeological methods and methodology. Specifically, these collaborations inspired the development of the catch-and-release surface collection strategy, a form of site survey and surface collection that provides for in-field curation of belongings back in their original locations after in-lab analysis and digital documentation. Initially developed as part of my dissertation research with the Kashaya Pomo Interpretive Trail Project, I have since worked with the Amah Mutsun Band of Ohlone and now Grand Ronde to adapt this method to the unique cultural and physical contexts of ancestral places in their homelands.

In-field curation is viewed as highly beneficial by the nations I have worked with, including Grand Ronde, who view the permanent removal of belongings as directly connected to negative health impacts. From an archaeological and museological perspective, we face a collections crisis that is compounded by both current approaches to cultural resource management and the continued emphasis in academic archaeology on collection of new data rather than re-examination of legacy data. That the Kashia, Amah Mutsun, and Grand Ronde nations, as well as several of the agencies they work with have adopted this method indicates catch-and-release’s wider viability as a culturally sensitive and sustainable survey method within heritage managers’ toolkits.

Can you tell us about your efforts to support and mentor students who are interested in archaeology and related fields?

Since 2015 I have co-directed Field Methods in Indigenous Archaeology (FMIA) with the Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde Community of Oregon’s Historic Preservation Office (HPO). A core element of this project is a five-week field school that trains undergraduate and graduate students in community-based participatory research methods, archaeological field techniques, and public science scholarship.

In addition to building the capacity of the Grand Ronde Historic Preservation Office to train its own future heritage managers, the program is a critical means of building the capacity of future archaeologists what it means to work with and for a Tribal Nation. Consultation with Tribal Nations is a big part of modern archaeology — also referred to as cultural resource management — in the US. Yet, there are currently only a handful of training opportunities that provide formal training in Indigenous or Tribal archaeology. Our field school fills a crucial gap in archaeology education.

We have trained more than 40 students through this program and more than 40% of our students are from communities who have been historically excluded from archaeology. For comparison, less than 10% of practicing archaeologists are Indigenous or come from a historically excluded community. In discussing with our students why they applied for and accepted admission into FMIA, students have specifically indicated that the field school made them feel like they could do archaeology in a different way, one they didn’t imagine was possible based on their own undergraduate and graduate experiences. They have also noted how it felt to be part of a community and not be the only one. This suggests that a key means of attracting — and importantly, retaining — students from diverse backgrounds in archaeology involves changing how we do archaeology so that it is more inclusive of and safer for a wider body of archaeologists. In making space for all participants to bring their full selves and structuring our relations around the values of respect, reciprocity, and care, I believe we have accomplished just that. And we’ve done so in ways that speak to how we might achieve these ends not just in Indigenous archaeology projects or field schools, but across the field.

It is a significant testament to the program and participants’ investment in FMIA that the vast majority of our students have continued to work as interns within my Pacific Northwest Archaeology Lab at UW, our Burke archaeology department, or as interns within the Grand Ronde HPO. While not all of FMIA’s students will continue in archaeology, students report that it has encouraged greater understandings of tribal sovereignty, specific knowledge of Grand Ronde’s own unique history, as well as created a personal awareness of the wide-ranging ethical and social impacts of archaeology and scientific research within indigenous communities. In providing both tribal and non-tribal students with opportunities to participate in indigenizing archaeology, we have had the opportunity to demonstrate the difference working with and alongside a community makes so that this lesson might, in turn, be demonstrated for others.

What’s your favorite object or belonging in the collections?

This is so tough because the Burke’s collections are so uniquely cool and I’m always discovering something new when I walk through the galleries or get the opportunity to learn from staff as they share our collections with our visitors! I might be biased here, but frankly dirt is one of my favorite items in collections because it preserves so much information that’s not immediately visible to the eye. From tiny seeds and nut shells and charcoal fragments to traces of shellfish and animal remains, when we start to examine dirt in more detail we start to get a rich record of past meals individuals, families, and communities shared. In turn, this information tells us about the local environment and how it may have or continues to change as our relationship to these places has shifted over time.

What are some of the most rewarding aspects of your work? Challenges?

By far the best part of being at the Burke is learning something new everyday. From archaeology to paleontology to the herbarium to exhibits and education, our staff are constantly showing each other how much knowledge is embedded in our collections. Quite simply, when I walk in the door, I get to be a kid again and learn about aspects of our state, of the world around us, and of the people and histories connected through our collections that I’d never imagine. The most challenging thing is to stay in my office and get my work done because there is so much to learn! I mean, who doesn’t want to go and see the mammalogy team preparing coyote specimens or learn from contemporary artists in our studio or check out a Burke Box?!

What are you reading currently and why do (or why don’t) you like it?

What are you reading currently and why do (or why don’t) you like it?

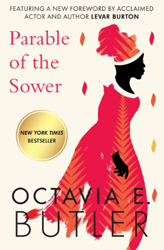

I’ve started re-reading one of my all-time favorite books: Octavia Butler’s Parable of the Sower. In addition to being a Seattleite, she had such a powerful way of writing about the world — specifically the material aspects of our world, our land, and our relations — that really speaks to me as someone who examines how humans’ relationships with and to their lands and waters have varied and changed over time.

"... when I walk in the door, I get to be a kid again and learn about aspects of our state, of the world around us, and of the people and histories connected through our collections that I’d never imagine."

About Sara Gonzalez

About Sara Gonzalez

Dr. Sara L. Gonzalez was appointed interim executive director of the Burke Museum of Natural History and Culture in March 2025. She joined the museum in 2020 as curator of archaeology and served as associate director for research and collections from August 2024 to February 2025. Dr. Gonzalez joined UW faculty in 2013 and is an associate professor in the Anthropology department, adjunct associate professor of American Indian Studies, and is currently appointed as a Mark A. Emmert Distinguished Professor. From 2021 to March 2025, she also served as the director of the Quaternary Research Center, an interdisciplinary environmental science center at UW.

An anthropological archaeologist by training, Dr. Gonzalez works at the intersection of Indigenous studies, tribal historic preservation, and public history. Her research contributes to the growing field of Indigenous and community-based archaeologies. These sovereignty-driven approaches are committed to the integration of Indigenous knowledges and research methods into archaeological practice and historic preservation and recognize the fundamental rights of Tribal and Indigenous Nations to determine how and in what ways their heritage is cared for and protected now and into the future. As a core feature of this work she explores the diverse applications of minimally- and non-invasive field methods and digital media as tools for tribal historic preservation. Alongside this research she developed and co-directed multiple community-based, Indigenous archaeology field schools, including Field Methods in Indigenous Archaeology with the Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde Community of Oregon. These programs train the next generation of archaeologists and heritage managers what it means to do archaeology with, by, and for a Tribal Nation.