The Burke’s new curator of fishes, Luke Tornabene, has a research focus on deep reefs in the Caribbean, so the last couple of years have brought a significant change to our collection. Imagine my joy when he asked me to participate in fieldwork in sunny Roatan, Honduras this past summer—fieldwork with no fleece or wool? Sign me up!

The main purpose of the trip was to set up a new base of operations in Roatan for the Smithsonian Deep Reef Observation Project (DROP) team. The team has been working in the southern Caribbean since 2011 using the submersible Curasub to explore the deep reefs below SCUBA diving range, using hydraulic collecting arms to collect specimens.

They have described dozens of new species from these dives, but also discovered that the animal life they were seeing at these depths was unique. They recently described a new zone of the reef community, called the “rariphotic zone,” which is a low-light zone from 130–300 meters (400–1,000 feet), below the reef-building coral zone.

Because the Curasub is limited to a depth of 300 meters (1,000 feet), they wondered just how deep the rariphotic zone goes and when it transitioned to the deep sea. Clearly they needed to get deeper! Enter the Idabel submersible—a privately owned, homemade submersible stationed in Roatan capable of descending to 600 meters (2,000 feet).

Luke worked with an engineer to install a suction-powered fish-catching system, similar to the Curasub, and collected a few specimens on a previous trip. The plan this time was to get down below 1,000 feet, see where the fauna starts to change, and collect as many specimens as possible. In addition, we’d record temperature data, which can be combined with similar data recorded from the Curasub to look for trends across the Caribbean.

My role in the expedition was to SCUBA dive with Luke to collect specimens for a side project while not in the Idabel. From collections made across the Caribbean, he and our colleagues are looking at a small goby called Risor ruber (less than 2 cm) that lives on many different species of sponges.

In their genetic analyses they found several distinct genetic lineages among what was historically considered one species. They hypothesized this goby had evolved into separate species by associating with different species of sponges, but this variation was very subtle and had been overlooked by scientists. Collections from Roatan would help to determine if this trend is found throughout the Caribbean.

After months of hearing that the trip was not likely to go due to a lack of permits from the Honduran government, we finally got the good news in April that we were clear to go in early June. With my new scientific SCUBA diving certification in hand, I could now go to Roatan as Luke’s dive partner to collect these gobies (and hopefully get down in the Idabel).

Luke and graduate student Rachel Manning headed out a day before me. One difficult part of fieldwork is that it takes you away from family. I had to miss my son’s birthday for this trip, so we had the party a bit early so I could celebrate with him. I promised to bring something special back for him as I headed out after the party on a red-eye flight to Roatan.

I was warned ahead of time about how dangerous it was to travel in Honduras, so I was a bit nervous. I was meeting DROP team member Ross Robertson at the airport, who flew in from Panama earlier in the day. Together we took a taxi over to Half Moon Bay to meet up with Luke and Rachel at our field site.

We arrived to find our hotel room transformed into a field station, with SCUBA gear and elaborate photography equipment combined with the wonders of a Styrofoam cooler and a few bowls and spoons from the kitchen to transport fish specimens. Empty plastic bottles were soon turned into anesthetic-dispensers to make catching tiny fishes from sponges easier while SCUBA diving. Necessity is truly the mother of invention when working in the field and the strangest of objects can become indispensable.

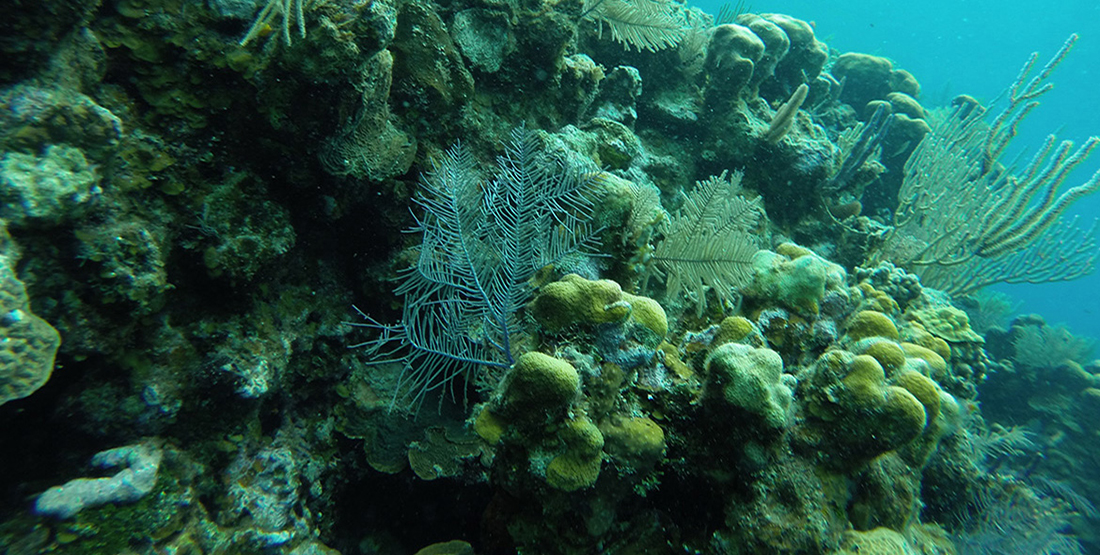

We found a dive shop that was willing to drop us off at dive sites while they took paying customers on guided dives. We made eight dives to collect tiny gobies from many different species of sponges ranging in depth from about 9–18 meters (30–60 feet).

On our first dive I was amazed to look up and see a giant Green Moray Eel (Gymnothorax funebris) swim around Luke while he was focused on the sponge. He never saw the eel, but I thought it was a great welcome to diving in Roatan. The diving was spectacular and I found myself wishing we could take a bit longer to look around. Scientific diving requires a lot of focus, but I made sure to pop my head up every now and then to marvel at the beauty around me.

We collected over 50 specimens of the goby we were looking for and were hopeful that these collections were going to solidify our theory once we were back in the lab. (Alas, upon our return to Seattle Luke sequenced the DNA from all of the specimens and found no variation—they are all the same species. More collections are needed at more sites throughout the Caribbean to understand what is going on with this group of gobies.)

The Idabel submersible in Half Moon Bay, Roatan, Honduras.

Katherine in the Idabel submersible getting ready to dive to 1500 feet.

I wasn’t sure whether I would get a chance to get down in the Idabel or not. I had been hearing all week about the dives and I had been helping to process the specimens they collected, including specimens of a new genus and several new species of gobies for Rachel’s graduate work. It wasn’t until the last day that I was lucky enough to get down in the sub myself.

Luke and I dove to 1,500 feet during a dive that lasted five hours. Diving with the sub through the depths that I had been exploring by SCUBA all week was beautiful, but to be able to keep descending into the dark and to see how the reef changed with depth was fascinating.

At one point on the descent the pilot turned out the lights so we could see bioluminescent animals in the dark. That had long been a dream of mine—to see bioluminescence for myself. I wish we had been able to stay in the dark longer to really appreciate the light show that animals put on in the deep.

Not long after we settled at 1,500 feet, the pilot called out that he saw a Roughshark (Oxynotus caribbaeus). I had never heard of a Roughshark and only later found out they are quite rare and known only from 400–450 meters (1,310–1,480 feet) in the Caribbean—exactly where we saw it! It was beautiful and strange, and really looked like it belonged in the deep.

We noticed as we moved around how desolate it appeared. I felt like I was looking at the surface of the moon. No animals were living on the rocks except for a few isolated glass sponges. We saw a few species of fishes that are known deep-dwellers and knew we had found the deep sea fauna separate from the rariphotic fauna.

As we ascended, more and more life was living on the rocks and the fishes looked more like shallow reef fishes—colorful and abundant. Rising back up into the sunlight felt triumphant.

Our trip was hugely successful in terms of the number of dives we made, the data we collected, and the number and quality of specimens we collected. Several new species are being described and the ecological data gathered will help inform our understanding of reef communities in the different photic zones across the Caribbean.

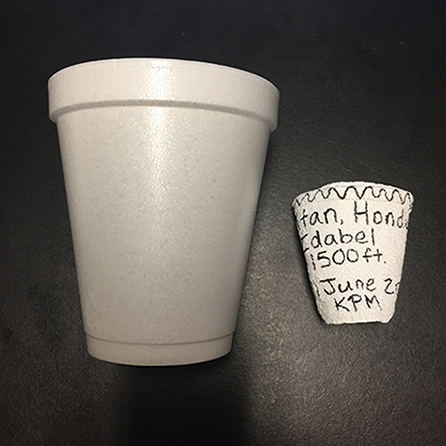

But home was calling, and I missed my family. I told my son I would bring him something special, so on our Idabel dive I attached some decorated Styrofoam cups to the outside of the submersible. The great pressure at these depths causes the Styrofoam to compress to a fraction of its original size, making a one-of-a-kind souvenir from the bottom of the ocean. I wish I could have shared the experience with him, but maybe this tiny cup will inspire him to live a life of adventure and curiosity.

---

Katherine Maslenikov has been the Collections Manager of the Burke's Ichthyology collection since 2001.