Ancestors

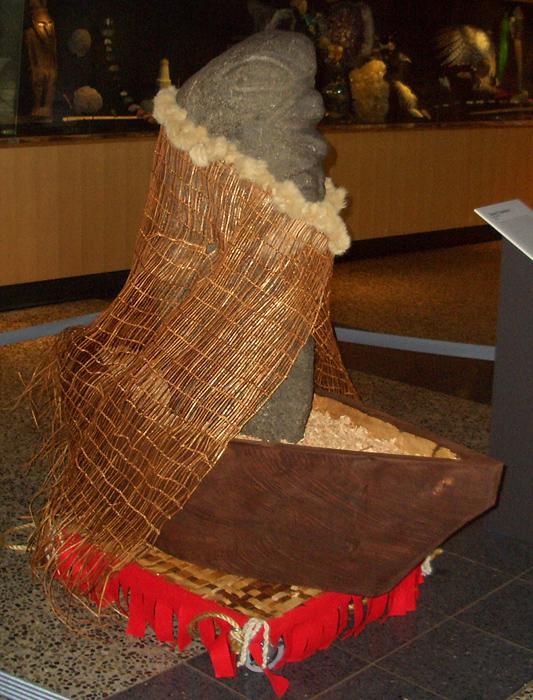

One such ancestor is known as T'xwelatse. Sto:lo history tells of T'xwelatse, a medicine man who settled on the shores of the Chilliwack River before being turned to stone in a transformation contest. “His story was passed down through time – even after the man was lost,” said Herb Joe, the former chief of the Tzeachten First Nation band. It has been 15 years since Joe inherited the name T'xwelatse and took on the responsibility of finding the statue.

“The god who turned T'xwelatse to stone told his wife to take the statue back to the village to put in front of her home as a reminder to all that we should live together in a good way. This was done, and T'xwelatse was used as a teaching icon for many years before he disappeared.”

In 1892, the statue, which is about 1.2 metres tall and 270 kilograms, was found by a farmer in a field in the Sumas Prairie. Eventually, a group of young naturalists acquired the statue and donated it to the Burke Museum in Seattle in 1904. “It was rediscovered by Herb Joe, who made it his life mission to return the stone to his people,” recalled Peter Lape, the museum's curator of archaeology. In 2006, the Burke Museum returned it to the Nooksak tribe, who in turn returned it to the Sto:lo people in British Columbia, where it originated.

Ancient Figures

Several ancient Coast Salish objects carved from elk antler show a human figure with its arms raised in a gesture that today signifies “thank you” to Coast Salish people. The Burke Museum has two such figures dated from 800 to 1,800 years ago. The comparison shows how consistent Coast Salish art remained over several hundred years.

Sucia Figure

Sucia Figure, 1200-200 CE. This is the largest of these figures. The eyes and hands were likely once inlaid with shell, and the holes at the sides of the head probably once had ear pendants. The shape of the head shows the head-flattening that was done on the Southern Northwest Coast as a sign of status and beauty. The skirt may represent the cattail or cedar bark skirts worn by women in ancient times. Burke Museum cat. no. 2.5E603. Photo: Burke Museum.

Bainbridge Figure

Bainbridge Figure, 1792. This human figure is raising hands in the same gesture found on ancient antler figures from this region. The hat has leather tassels strung with dentalium shells and copper squares are inlaid in the hat and shoulders. The torso held a rectangular mirror, that still survives. Mirrors and sheet copper were highly valued trade items, acquired from British and American maritime fur traders in the late 18thcentury. British Museum cat. no. VAN160. Photo: British Museum.

Textile History

Throughout ancient times and into the early 20th century, Coast Salish women produced a variety of textiles from the wool of mountain sheep and small “woolly” dogs raised specifically for this purpose. Though the woolly dog is now extinct, mountain goat wool is highly prized and remains an important ritual material used in religious ceremonies.

In the early 20th century, plain, twill-woven robes with simple colored stripes were gradually being replaced by commercial cloth. However, toward the end of the century, Coast Salish weavers revived the weaving tradition.

This twined mountain goat wool robe was collected by the Wilkes expedition in 1841. National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, cat. no. 1891.

This Snohomish twill-woven mountain goat wool robe was collected by James T. White of the Young Naturalists Society. Burke Museum, cat. no. 3.

Basketry History

Basketry is one of the oldest art forms on the Northwest Coast, dating back at least 5,000 years. The oldest Coast Salish basketry was discovered at an archaeological site of a former fishing camp along the Olympic Peninsula’s Hoko River and is approximately 2,500 years old. Twined cedar bark hats also have an ancient history on the Northwest Coast. The oldest existing hat, known as the Wapato Creek Hat, is from 1450-1620 CE. In 2000, the Burke Museum commissioned Karen Reed, Puyallup/Chinook weaver, to replicate this hat, excavated at the mouth of Wapato Creek, where her grandmother had lived.

True to its ancient prototype, it is a double hat with the inner and outer hats woven with a continuous warp that doubles back and joins the outer hat near the crown of the hat. The unusual shape of this hat, with its pointed crown and convex brim, differs dramatically from the traditional shape of Coast Salish cedar bark hats known from the 19th century, and represents an archaic form more closely resembling the flared flat-topped hats from the northern Northwest Coast.

Nineteenth-century Coast Salish hats were double hats (inner and outer hats joined at the crown) with a rounded dome-shaped profile. Double thick and tightly twined, they were an efficient and elegant rain hat. Learn more about Coast Salish weaving techniques.

This ancient hat was excavated from an archaeological wet site at Wapato Creek in 1976, along with remnants of a fish weir and fiber netting. Though it is crushed and damaged, this unusual hat retains enough of its original shape to allow contemporary weavers to study its ancient style. The blackened color is from the polyethylene glycol used to preserve it after removal from the wet site. Burke Museum cat. no. 1983-72/1.

The unusual form of this hat is based on an ancient hat excavated at the mouth of Wapato Creek where Karen Reed's grandmother lived. True to its ancient prototype, this is a double hat with the inner and outer hats woven with a continuous warp that doubles back and joins the outer hat near the crown of the hat. Burke Museum cat. no. 2000-124/1.

Coiled cedar root basket made by Mrs. John Goody (Siagut), Cowlitz/Nisqually, collected by Judget Wickersham, 1890s. Burke Museum cat. no. 2005-21/1.

Twined double cedar bark hat from the late 19th century. Seattle Art Museum cat. no. 96.98.

Totem Pole History

Coast Salish artists did not carve tall wooden heraldic poles, known as totem poles, until the early 20th century. In earlier times, interior house posts were sometimes carved with human figures and other "spirit helpers" or abstract images referring to the spirit power belonging to the owners of the house. These were different from crests, figures of birds, sea creatures, and other animals carved on totem poles from the northern Northwest Coast.

These and other ceremonial artworks, such as rattles and ceremonial garments, were not meant to be public, and were used only on ceremonial occasions, sometimes being destroyed after the death of the owners. For that reason, such objects are not found in large numbers in museum collections. Those that are housed in museums are not publicly displayed without the permission of the associated tribes or families.

In 1899, the Seattle Chamber of Commerce removed a pole from the Tlingit village of Tongass in Southeast Alaska without the knowledge or consent of the owner, Kinninook. The pole was erected in Pioneer Square in downtown Seattle in 1899, and thereafter became a symbol of the City of Seattle, whose businessmen were promoting the city as a gateway to Alaska. The 1909 Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition held in Seattle used this totem pole as part of its promotional efforts, making it a symbol of the fair as well as the city. Models of this totem pole as well as others from British Columbia and Alaska were sold in large numbers as souvenirs to tourists.

Because of this, people came to expect Native artists from the Coast Salish area to carve totem poles, in spite of the fact that this was not part of their artistic tradition. In response to this public demand as well as to raise awareness of the First Peoples of western Washington, Chief William Shelton at Tulalip and Joseph Hillaire at Lummi began carving Coast Salish-style story poles in the 1920s and '30s.

For more information on totem poles, visit “The Enduring Power of Totem Poles.”

See More Coast Salish Art

Continue exploring the history of art in this region, what makes Coast Salish art distinctive among the many regional Northwest Coast styles, and the vitality of contemporary Coast Salish art.

Additional Coast Salish Art Resources

Search additional resources related to the First Peoples who speak the Coast Salish language.