In October 2014, "nature news" outlets made a big deal of the "discovery" of a "puppy-sized" tarantula. The Theraphosa species concerned has been well-known for 200 years; at a maximum weight of 6 ounces, any comparable puppy would have to be awfully small!

A correspondent had heard that "tarantulas crawl out of their skin before dying." Like all other spiders, tarantulas do molt their "skin" a number of times while growing, but not just before dying, unless (as sometimes happens) they die of molt failure. A stranger myth about molting is that "the brown recluse is the only spider that sheds its skin." Nope - they all do.

Brown recluses seem to accumulate myths. In 2005 a man reported hearing that they acquired their toxicity through a mutation due to World War II atomic-bomb research. Of course that is nonsense – the toxic component in recluse venom is also present in distant relatives that diverged many millions of years ago. Once in a while you hear a rumor about a supposed cross between a black widow and a brown recluse (those being the only 2 spiders the rumor-monger has ever heard of). These species are so unrelated it would be like a cross between a whale and a walrus. One person heard from a Missouri ER doctor that a brown recluse "would return to the person he had bitten" — in 2013! Sounds more like what doctors believed back in 1320.

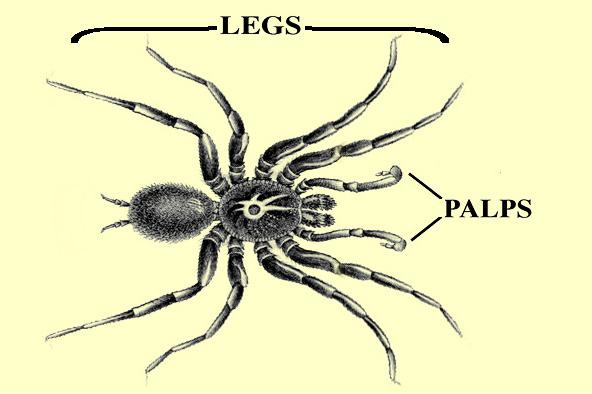

One occasionally hears a report of a ten-legged spider. One man wrote me that his son had heard about such a spider on a television documentary. Such reports involve certain spiders of the mygalomorph (tarantula-like) suborder that have unusually long pedipalps, which non-arachnologists can mistake for a fifth pair of legs. All spiders have palps (click here for a diagram of normal palps), but in the vast majority they are too small to be mistaken for legs.

Pink toe tarantula, Avicularia avicularia (Brazil to Trinidad, body length 6-7 cm).

Macrothele calpeiana (historic drawing) (Spain) showing long palps that can be mistaken for legs.

Female wolf spider with about 100 spiderlings riding on her abdomen.

Another man's son found a "one-eyed spider" on a web site, but couldn't find the site again. While there is a slight chance of a "freak" spider specimen with only one eye (of the normal 8) present, this is more likely a case of a trapdoor or similar spider, in which the 8 eyes are clustered very close together on a central "bump," easily misinterpreted as a single eye.

A correspondent states that the saying "A spider by day is quite okay, but a spider at night should cause you flight" was common among early 20th century European immigrants to New York City. More recently someone else explained this as a mistranslation of a German saying that begins "Spinnen am Morgen bringt Kummer und Sorgen…" The word Spinnen means both spinning (the usual translation) and spiders.

Persons recovering from Latrodectus (black widow and related species) bites are sometimes told by well-meaning friends that if they are bitten again they will probably die! There is no medical basis for such a belief.

Brown widow spiders, Latrodectus geometricus, allegedly appeared for the first time along the gulf coast of the USA due to the severe hurricanes of 2005. Residents of these areas (who already had enough troubles) received multiple warnings about this "dangerous" species. In reality the westward spread of this species from long-established Florida colonies was well under way before 2005. Symptoms of its bite are much less severe than those of black widows that always existed in these areas, so there was no reason for the hype except to sell newspapers.

A correspondent heard the story "baby spiders don't know how to control their venom, and may inject more than an adult" on a California ranch in the early 1990s. Spiders don't actually have to learn biting behavior – they are hatched with all such abilities already hard-wired. And spiderlings don't have enough venom to matter anyway. A similar myth is told about baby snakes.

A December 2014 correspondent heard from a 10-year-old boy that "spiders are born with all the venom they'll ever have." Questioned, the boy said he'd read it in "lots of places." I haven't located any of those places yet, but spider venom is secreted by glands that make more after every use. Venom is mainly proteins, which certainly would not last for a typical spider's one-year lifetime. And to quibble, spiders are hatched, not born.

A Canadian correspondent has heard people say that stepping on a spider will bring some catastrophe like bad weather or a broken back. Another writes of hearing this applied to harvestmen in NE Ohio.

A comment posted to an Australian web site states that the venom from a wolf spider bite "eats a centimetre of skin every month" and "in seven years ... you could have no arm left." Not only is this medically ridiculous, but no wolf spiders have been proven to have dangerous venom of any kind.

I've heard the "spider urine" myth once from the USA and several times from Latin America, where it probably originated. It seems that there are one or more spider species that urinate on sleeping persons, and the urine, rather than a bite, causes a skin ulceration. In Guatemala this myth (still going strong in 2008) centers on a tarantula species locally called araña de caballo (horse spider) which is said to cause severe hoof and leg trouble in horses and other livestock by urinating on them. In truth, spiders do not have separate urine and feces, and their droppings consist largely of guanine, which is a component of DNA and found in all living things; highly unlikely to cause any skin reaction!

One woman wrote of her husband's belief that "all 'sticky' spider webs are from poisonous spiders." Quite untrue - the most commonly encountered webs with sticky silk are made by orbweavers, none of which is medically significant.

In late summer 2015, a Wikipedia vandal added fantastic new rumors to the article on Castianeira, a genus of ant-mimic spiders. False statements included: that the spiders were brought to North America from Australia by drug cartels; that female Castianeira castrate their mates; that it was a Castianeira that bit Peter Parker in the Spider-Man franchise. The original faked article didn't last long, but echoes of these rumors remain, all started by this one person. Lest there be any doubt: Castianeira are not "castrating females," and the genus is native to North America—not to Australia!

Finally, a really strange one: "From time to time, spiders breed by cloning. That is, the mother makes several clones of herself inside her body, and when the spiderlings grow they start to eat the mother until the mother is just an empty shell. You see this sometimes when you try to smash a spider and out of the smashed spider, hundreds of spiderlings creep out." At least three later correspondents related this to a real experience of stepping (shame on you!) on a female wolf spider carrying a brood of young on her back. Surviving young would scatter from the maternal corpse, but they weren't inside her.

Spider Myth Resources

Explore even more! Additional spider resources and more myths (poor spiders can't catch a break!).