Researching the Risks

In addition to solving the Big One mystery, lots

of research is going on right in our own backyard.

|

Seattles Kingdome imploding.

When Seattles Kingdome was scheduled for implosion

(the opposite of explosion), one study placed seismographs

in backyards and schools around the Seattle area. The results

are helping to create a detailed picture of which neighborhoods

are most vulnerable to earthquake shaking.

|

Uncovering the Seattle Fault

|

The discovery that a Big One really had happened in the Pacific

Northwest prompted new interest in our regions geology.

Within a few years, reseachers found evidence of another great

earthquake, one that took place 1,100 years agoright

under Seattle.

Unlike the big subduction zone earthquake in 1700, this one

was centered on a fault that lies close to the surface. Thats

significant. Movement along a shallow fault can cause very

intense shaking, and the Seattle Fault runs through one of

the most heavily populated parts of Washington. There are

shallow faults beneath Tacoma and Whidbey Island as well.

The information we get from studying the Seattle Fault helps

predict earthquakes throughout the Pacific Northwest.

In order to better understand the risks to communities, scientists

today are making use of ingenious new approaches to map the

geologic structures beneath Puget Sound.

|

|

|

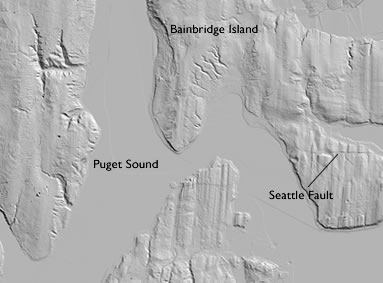

LIDAR (Light Distance and

Ranging) technology uses airplane-flown lasers to reveal

surface features hidden by buildings and vegetation. This

map traces part of the Seattle Fault.

|

Quakes in Eastern Washington

|

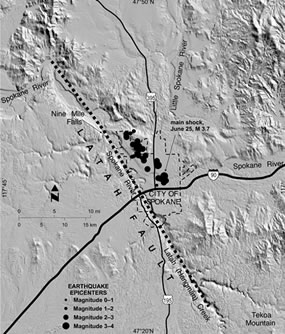

Although

the risk is greater west of the Cascades, the Columbia Plateau

also is geologically active. The ground shaking that took place

in Spokane in the summer of 2001 was a reminder that Eastern

Washington has earthquakes, too. In fact, a very large earthquake

occurred near the southern tip of Lake Chelan in 1872, and a

moderate earthquake damaged Walla Walla in 1936.

Just a few months after the 2001 Nisqually earthquake, Spokane

experienced a series of small, shallow, closely spaced earthquakes

that geologists call a swarm. More than 80 small

earthquakes were recorded by the end of 2001. The largest quake

of the swarm was a magnitude 3.9. Another notable swarm began

in November of 1987 near Othello, Washington. That series of

200 quakes took place over nearly a year. |

Aerial

image of Latah Creek in Eastern Washington

Straight lines are rare in nature, and may be signs of an underlying

fault. Some geologists believe a fault beneath Latah Creek is

responsible for the recent earthquake swarm in Spokane. |

|

Portland's Shallow Faults

It can be difficult to find surface faults in the tree-covered

Northwest. Today, hidden shallow faults can be seen

by a variety of new technologies, including those that use the natural

magnetism of rocks. In the Portland-Vancouver area, studies revealed

the almost-straight line of the Portland Hills fault zone. If this

fault becomes active, it poses significant seismic hazard to the

communities near Portland, Oregon, and Vancouver, Washington.

|

Red line shows the Portland Hills fault zone.

|

|