What is your research on?

I study the fossil record to see how climate change affects animals over time. In my dissertation research at the University of California, Berkeley, I focus on reptiles because they are particularly sensitive to changes in climate. They cannot generate their own body heat metabolically, the way you and I can. Reptiles compensate for this in a lot of ways that affect their ecology (their interactions with their environment and other organisms).

This means that I can’t interpret climate change effects on past reptiles from the fossils alone. I have to understand how living reptiles function. Thus, I also study modern reptiles, and how they are responding to climate change today.

What sort of specimens are you looking at with the Burke VP Collections Grant?

I am looking at fossil reptiles—specifically, lizards, crocodylians, and turtles—that lived in the Western Interior of what is now the United States from about 66 to 23 million years ago. The Western Interior is well represented through an interval of time called the Paleogene. This interval is well represented in the Burke Museum vertebrate paleontology collections, including a rich sample from the time just after that rapid warming event. This is what made me want to visit the collections.

The Paleogene is an interesting time to study because global climate changed dramatically during that interval—including an abrupt warming event around 55 million years ago. That warming was not even as rapid as what we are seeing right now, but it is the only warming event since the dinosaurs that compares in rate and magnitude.

How does the specific way that the Burke collects specimens aid in your data collecting?

The Burke Museum has always done a very thorough job of sampling its localities. Burke Museum paleontologists never just collect one type of animal—they collect all of the fossils that they find in a given location. Furthermore, they don’t split up the types of fossils they found when they curate them in the Burke collections. Instead, they keep everything found in a particular locality together.

Having all of the fossils from a particular locality together gives me a more holistic sense of what that place was like at that time. I can see everything that was living in the same environment as those reptiles, and potentially interacting with them. When the localities are also organized chronologically, as they are in the Burke vertebrate paleontology collections, I can trace how those communities changed over time.

What did your time at the Burke add to your research?

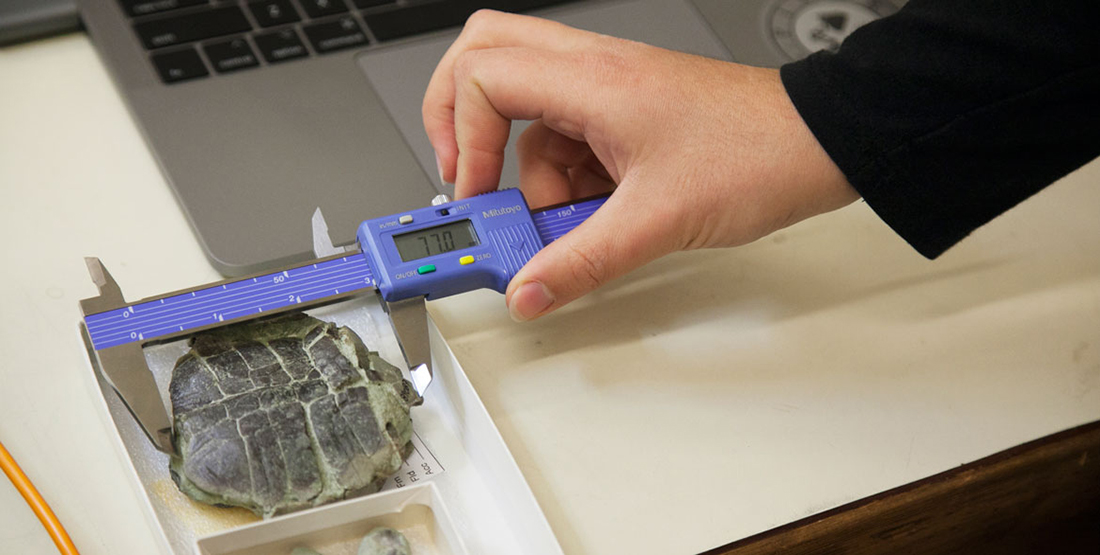

I got a lot of great specimens out of the Burke VP Collections, both in numbers and in quality. There were so many well preserved lizard and crocodylian skulls that I didn’t have time to measure them all, even after a week! I plan to return for a few days in February to finish up.

How do you hope your research on climate change can aid with understanding its effects today?

If we can understand how reptiles responded to climate change in the past, we can better predict how climate change will affect reptiles now. Reptiles are essential components of any ecosystem in which they occur—as key food sources, for example, or as top predators. Anything that happens to them will affect other organisms as well.

I also hope that this research can be a model for future studies that continue to investigate climate change effects over time and space using the fossil record.

Read about our other VP Collections Grant recipients this year, and learn more about Vertebrate Paleontology.