Our knowledge of the baby Triceratops is increasing, thanks to a recently-discovered baby Triceratops neck frill at the Burke.

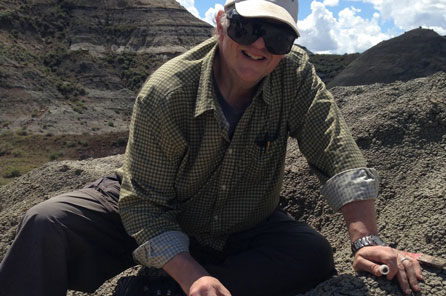

On a blistering hot summer day in 2016, an international team of paleontologists were working in Montana’s Hell Creek Formation—the most famous dinosaur excavation area in the world. Burke Museum Curator of Vertebrate Paleontology Greg Wilson leads the team for the Hell Creek Project, a multi-disciplinary project examining prehistoric vertebrates, invertebrates, and the geology of the area. Parts of the Hell Creek Formation are managed by the Bureau of Land Management, and Greg's team visits the area every year to collect new samples under a paleontological permit.

That fateful summer day, the team was exploring a section of Hell Creek that they hadn't returned to in 15 years. It was a few miles north of a ranch house, up and down ravines across the ranchland and into badlands. They were busy at work finding specimens like broken adult Triceratops skulls and prehistoric aquatic reptiles, when suddenly Ian Morrison, fossil preparator at the Royal Ontario Museum (ROM), called the team over. He was inspecting a little knob in the area that looked curious.

At first glance, it was determined to be a piece of an ordinary turtle shell, until members Mark Goodwin and Dave Evans looked it over and excitedly proclaimed it was much more than that. Mark, the Assistant Director at the University of California Museum of Paleontology (UCMP), was part of the team that discovered and described a complete baby Triceratops skull in 2006. Mark confirmed that the knob was indeed a frill that belonged to a baby Triceratops—making it only the fourth specimen of its kind ever found!

With only a few specimens to learn from, paleontologists still have many questions about how Triceratops grew and matured.

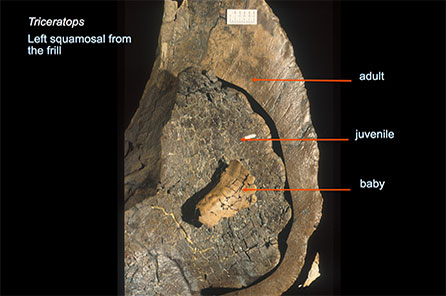

The new Burke specimen marks one of the smallest individuals discovered, and gives us another step in the chain from baby to juvenile to adult Triceratops. This specimen is a left squamosal bone of the skull—one of the three bones that came together to form the frill (or shield) that is characteristic of Triceratops. This sample supports the observation that dinosaur skulls like the Triceratops changed shape as they reached larger size.

Ian Morrison next to the Triceratops specimen after finding it

A comparison of the left Triceratops squamosal between baby, juvenile, and adult.

The UCMP specimen showed that the frill and horns characteristic of Triceratops was not just an adult feature (although, relative to the rest of the skull, the frill was not as big in babies as it was in adults). Because they appear in babies, scientists have cast doubt on the hypothesis that these frills and horns developed for sexual display only in sexually mature adult individuals.

An alternative hypothesis suggests that the frill and horns might have helped Triceratops juvenile species recognize each other, and help adults recognize other adults in visual communication and to signal changing sociobiological status.

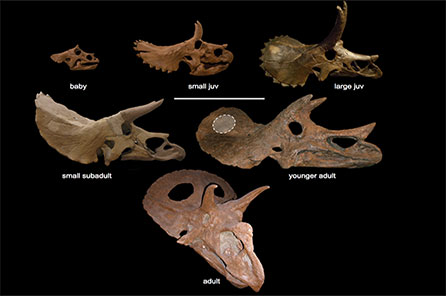

The proposed growth of the Triceratops skull.

The brow horns growth from Triceratops youth to adulthood.

With this baby Triceratops fossil at the Burke Museum, the paleontology team can contribute to various other hypotheses. There’s the possibility that the Triceratops and their young may have been as colorful as their living descendants, the birds. The baby specimens also reveal that the distinctive feature of the Triceratops—the brow horns—started straight and short in the baby, but grew long and curved as they reached adulthood.

The Burke specimen will continue offer valuable insight into the development of the Triceratops' youth. We’re so excited to discover more about one of our favorite dinosaurs!

---

See more from Vertebrate Paleontology.