Megan (Meg) Whitney, a graduate student in the UW Department of Biology, joined Christian for her first trip to Antarctica. Meg’s interest is in anatomy, but she didn’t want to be a medical doctor. “I wasn’t a dinosaur kid—I fell into [paleontology].” Meg is studying the anatomy of fossil bones and teeth at a microscopic scale to understand how animals were affected by extreme seasonality at polar latitudes as part of her PhD.

Christian and Meg were joined by paleontologists and geologists from the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, the Field Museum, Southern Methodist University, and the Iziko South African Museum.

After arriving at McMurdo Station and completing two weeks of trainings, the team flew to what would be their home for the next 45 days—the temporary Shackleton Glacier camp about 300 miles from the South Pole in the Transantarctic Mountains.

The base camp was a pop-up community for the research season. Camp staff are brought in to prepare food, maintain supplies, monitor the weather, offer medical support, pilot the helicopters and planes, and help with everything the 12 research teams might need to operate for months at a time.

Camp staff and fellow researchers become close friends—an extended family of sorts—especially since the research team celebrated the Christmas and New Years holidays thousands of miles away from home.

Each day, the paleontologists loaded all of their safety gear to take with them in case bad weather rolled in. Two weather forecasters in the camp kept an eye on any approaching weather that might impact the team’s ability to get in and out in the field safely. They also had a mountaineer accompanying them for safety.

The only way to reach the mountainsides where they were working was by helicopter.

It’s “kind of like catching an Uber,” added Meg. “Some days were longer, some shorter, dependent on the availability of helicopters that day and the weather."

The weather worked in their favor most of the trip and they only had to cancel three field days.

In addition to the weather, light conditions play an important role in spotting fossils.

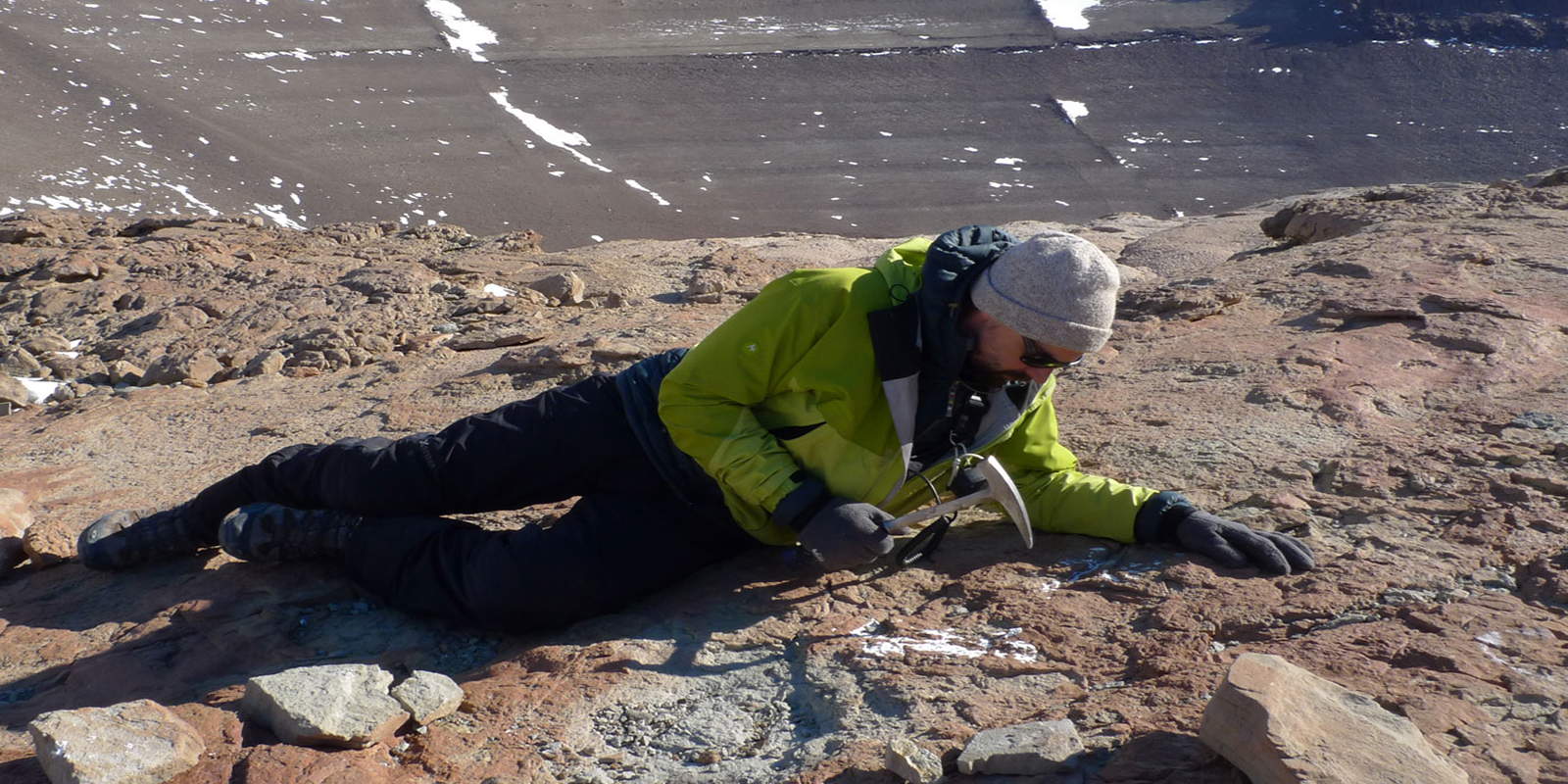

“We’re working on the mountainsides—the tips of mountain sticking through the glacier,” said Christian. “We use our knowledge of the geology and sedimentology to understand where fossils are likely to be found.”

“When we find a fossil, hopefully we’re finding the beginning of a skeleton and can trace that to the hillside and excavate a big block, including the fossil but also some of the rock surrounding it so it’s protected,” he said.

They focused their efforts on the Fremouw Formation, a rock formation that is about 250–240 million years old and use rock saws to excavate fossils to speed up the process.

“After we’ve cut out and chiseled out all of this rock, we put a plaster jacket on top which is an interesting thing to do in Antarctica, because it requires putting your hand in water, so you’re freezing your hand to make the jacket,” said Meg.

The Shackleton Glacier area was previously explored by paleontologists only three other times, in 1970–71, 1977–78 and 1995–96. “I was worried that it might have been picked over [by the previous teams],” said Christian. Thankfully that wasn’t the case.

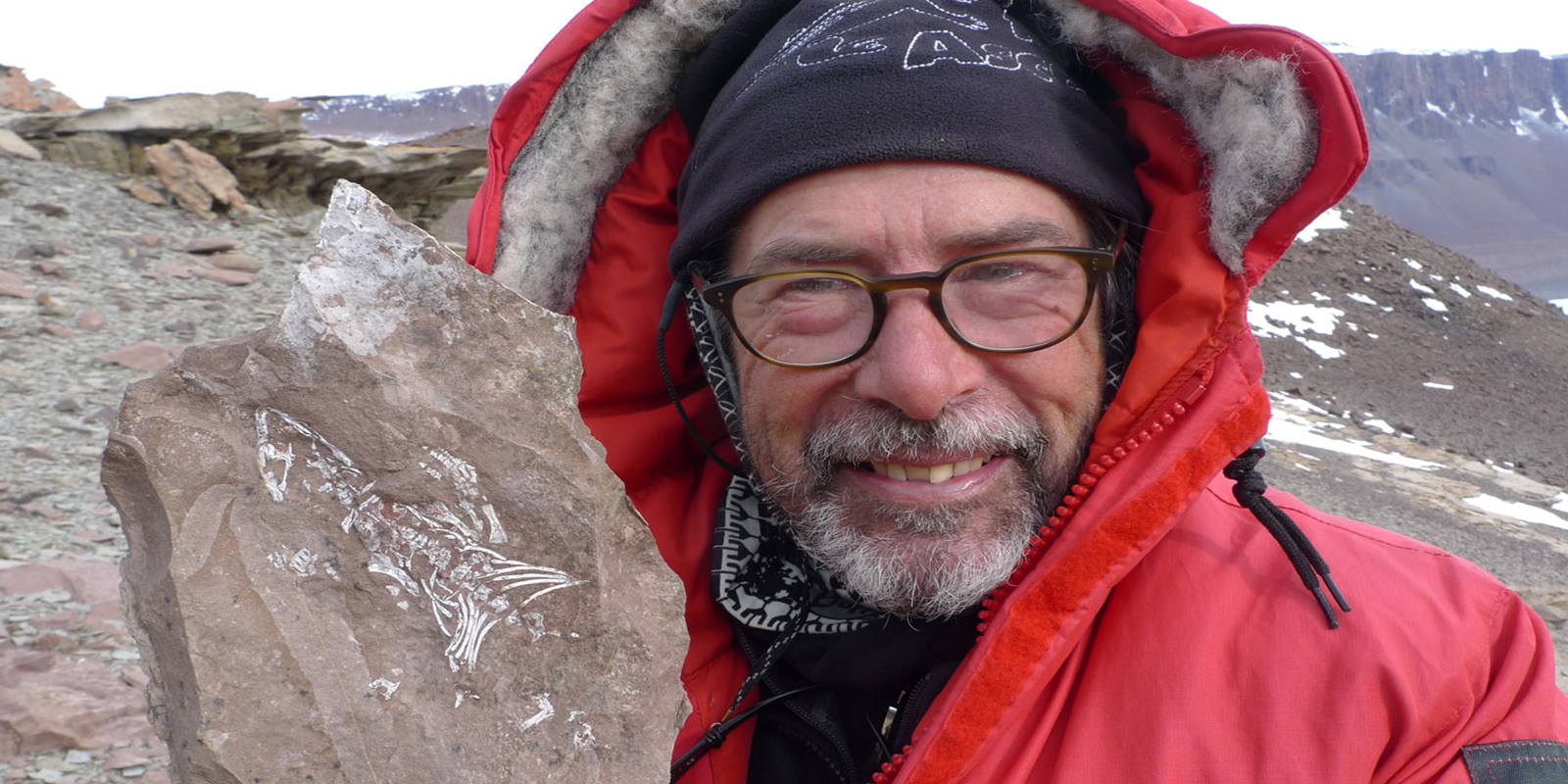

The team found fossil bones, trace fossils including tracks and burrows, and plant impressions—all indications of what life was like about 250 million years ago.

The skeletal material includes small, salamander-like amphibians (temnospondyls), early reptiles such as Prolacerta and Procolophon, in addition to mammal relatives like Lystrosaurus and Thrinaxodon. They also found several other species that will need additional research to determine what they were.

Fossils collected in Antarctica fall under the Antarctic Treaty, of which the United States is a signatory. This means that scientific observations and research must be made freely available. So the fossils will be cared for in the Burke Museum collection, but they will be accessible to any visiting researcher.

Not much is known about Antarctic amphibians, but Christian believes that will change after this expedition. “In the past, we’ve known which families of amphibians have been there but not which species,” he said. “Because we have so many [amphibian fossils] and they’re so well-preserved, we’ll be able to tackle that question and know what species of amphibians were in Antarctica after the mass extinction.”

In addition, they collected the first identifiable vertebrate fossils from the middle of the Fremouw Formation, which will help narrow down the age of those rocks. Fossils were previously found in the lower and upper parts of the Fremouw Formation, but not in the middle.

In all, the Burke Museum team found 56 new localities and more than 100 specimens, including two new localities, where vertebrate fossils had never been collected before.

The work is just getting started back at the museum now that the fossils arrived.

“Antarctica provides our only window into what happened to life at high latitudes after the Permo-Triassic mass extinction, and so I’m excited to be back at the Burke and get the lab work started,” said Sidor.

---

Read more about the team's findings in The Antarctic Sun article "Paleo Gondwanaland Was Full of Lystrosaurs."