Boas, Dr. Bunn-Marcuse explained, carried a 16mm camera and wax cylinders for sound recording with him on his last trip to the Pacific Northwest in 1930. At the Kwakwa̱ka̱'wakw village of Tsax̱is (Fort Rupert), British Columbia, Boas worked with George Hunt and other members of the extended Hunt, Knox, and Wilson families to record material for a never-finished study of rhythm and gesture. The product was 51 minutes of film clips showing technology, games, speech-making, and hereditary dance privileges.

For the last several months I have assisted Dr. Bunn-Marcuse with the early steps of publishing Ka̱ns Hiłile (Making it Right) as a digital book with University of Washington Press. As Dr. Bunn-Marcuse pointed out in her presentation, publishing Ka̱ns Hiłile (Making it Right) as an online book means that readers can encounter film clips such as this alongside audio, images of the dancer’s regalia, and text from Dr. Bunn-Marcuse and members of the Kwakiutl First Nation.

This will be the first time all these materials have been united since the film was taken. Most importantly, publishing Ka̱ns Hiłile (Making it Right) online means that all information uncovered by this project will be available to Kwakwa̱ka̱'wakw community members and the U’mista Cultural Center in order to meet community needs.

A primary goal for Ka̱ns Hiłile (Making it Right) is to provide links or citations to as much original material as possible so that anyone who wishes to carry out further research will not have to start from scratch.

One of my responsibilities for this project is to build the digital collection of images and objects that will appear in the final published book and to upload the collection to Omeka, an online content management system. It would be irresponsible of me to simply upload these materials to the online collection without also including information about where they come from, however.

Instead, when I import files into Omeka I also include metadata (literally “data that describes data,” or information about the items that the digital files represent) using the Dublin Core schema. This includes basic details about the item’s name, creator(s), and date of origin, but it also includes information on where to find the physical object, who owns the rights to it, and the category of file.

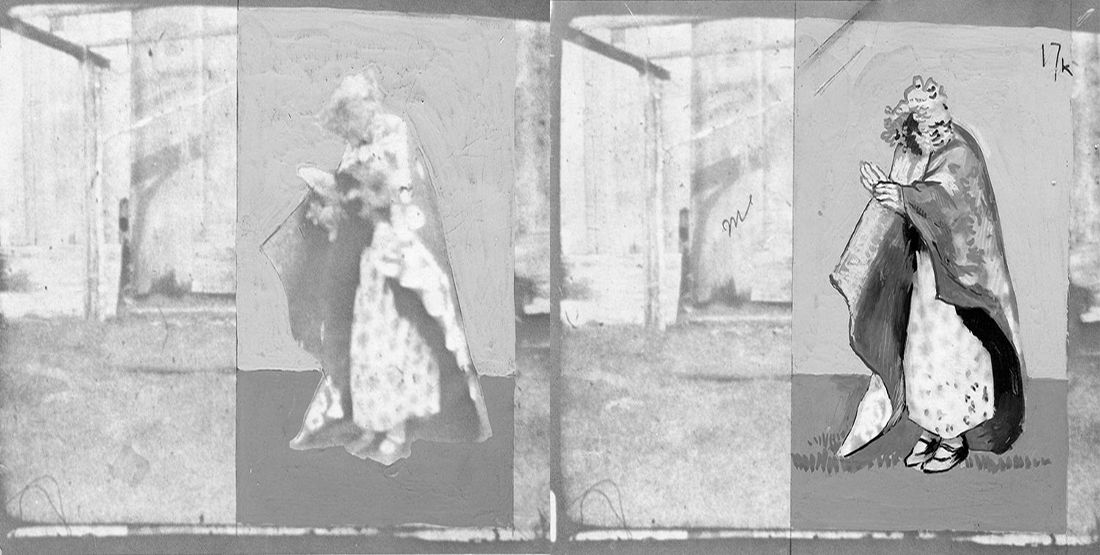

Take this image, item 2011-82-1 in the Burke Museum collections. This image is a digital copy of a frame from the same clip above that American artist Stuyvesant Van Veen has overlaid with a drawing, a work on progress of an illustration of the dancer from the film.

My spreadsheet for the set of images from which this item comes includes a title for the image, the name of the artist, an approximate date for its creation (mid-1930s), and the file type (.jpg) as well as the identifying number. All of this information is important for people who may want to visit the Burke in order to see the image in person.

Putting all this into a spreadsheet is not as simple as it sounds, however. Just like an archivist or museum curator who creates a record for a new object in a collection, I (and the author) have to make decisions about who should get credit for creating the item and to whom it belongs. Is Van Veen the sole creator, for example, or should we credit Boas because the illustration is based on the frame of a film he made? Is the dancer—Mary Hunt Johnson—also a creator? Her performance is the subject of the image, after all.

These are some of the questions that someone had to ask about every item in the Burke’s collections when it first entered them museum. Continuing to ask these questions every time we use these items is important for this project because most of the materials that will go into this book represent knowledge that belongs to the Kwakwa̱ka̱’wakw community at Fort Rupert but has been stored for decades at institutions far from Vancouver Island, where most people could not access them.

Publishing Ka̱ns Hiłile (Making it Right) as free, multimedia book that embeds the film, audio, and Kwakwa̱ka̱’wakw objects into the text is one way to elevate access to the knowledge and practices that these materials embody hand in hand with cultural context.

---

Learn more about the Ka̱ns Hiłile (Making it Right) project.

Read more from the Bill Holm Center for the Study of Northwest Native Art.

Madison Heslop is a PhD candidate in the Department of History at the University of Washington.