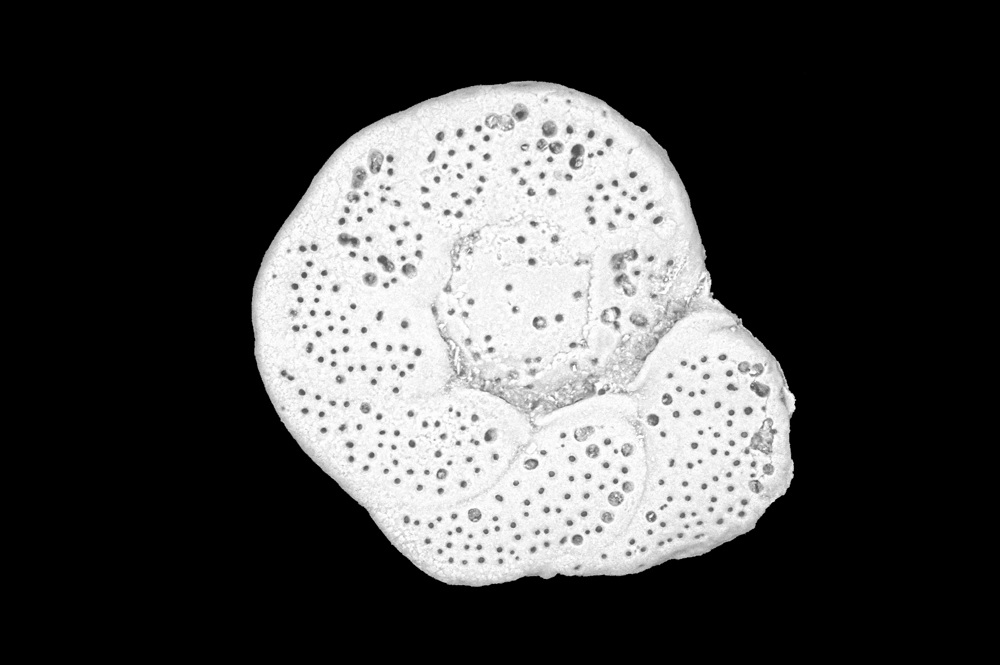

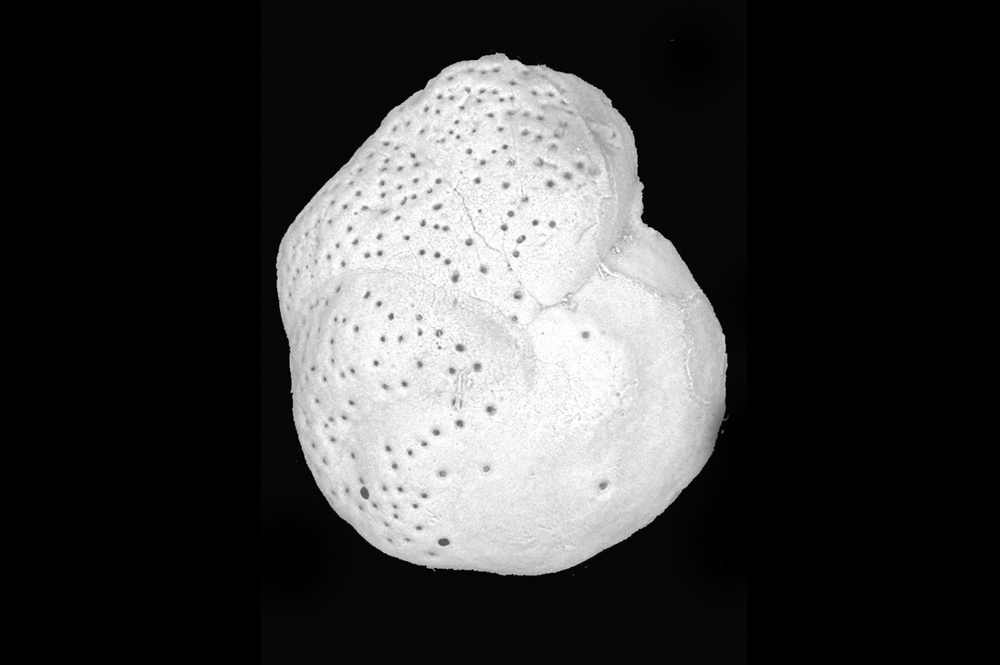

The shells have hundreds of tiny holes called foramen, the Latin word for window.

The organism pushes extensions of its cytoplasm called pseudopodia (or false feet) through these holes to gather food.

What do they eat?

Foraminifera eat detritus on the sea floor and anything smaller than them: diatoms, bacteria, algae and even small animals such as tiny copepods.

What eats them?

In turn, forams are devoured by grazing animals such as snails, sand dollars, sea-cucumbers and scaphopods (tusk shells).

How do they build their shells?

Forams are unusual among single-celled organisms because they build shells made of calcium carbonate (calcareous) or from tiny grains of sand stuck together (agglutinate). Despite their small size and relatively simple biology, forams build complex shells, consisting at their simplest of one chamber (like a vase or tube) to many chambers that coil in elaborate ways.

Where do they live?

Benthic foraminifera live in a number of different habitats at the sea bottom and most ‘crawl around’ using their pseudopodia. Some species live on the sediment surface (epifaunal) some within one or two centimeters of the surface (infaunal), some creep up stalks of seaweed or sea grass and others use organic “glue” to attach themselves to shells, stones, or even other forams.

Are there fossil forams?

When the foram dies, its shell may be preserved in the sea floor sediment where it becomes part of the fossil record as sediment turns to rock. Fossil foraminifera have been found in rocks as old as 500 million years, and it is highly likely they lived even further back. The Burke Museum has a large collection of fossil forams from West Coast marine sedimentary rocks.

What can this tell us about Puget Sound?

Foraminifera can be very sensitive to their environments. Some can only live where the water is clean and unpolluted. Others are more tolerant and can live almost anywhere. Certain species move into polluted places where others cannot live, and there are even alien invaders, brought here on ships from other countries. By documenting what species are living in certain areas, we can assess whether the sediments are polluted or pristine. See the illustrated guide to benthic foraminifera of Puget Sound for more information.

Elphidiella hannai. This is one of the three most common species found in Puget Sound, along with Elphidium excavatum and Eggerella advena. This species lives on the sediment surface or creeps along on vegetation, browsing for food. It is found in estuaries throughout the United States.

Deformed specimen. This specimen of Elphidiella hannai shows an irregular growth pattern. This can happen naturally, but can also be indicative of toxic chemicals or metals such as mercury and cadmium. Deformities are not common in Puget Sound, and cannot reliably be correlated with pollutants, thus they may be natural occurrences.

Dissolved specimens. Dissolution of foraminifera shells occurs when the acidity of the surrounding water is bad enough to eat away at the calcareous shells. We see this in the more industrialized parts of Puget Sound, particularly Bellingham Bay, Commencement Bay and around Bremerton.

Elphidium excavatum. One of the three most common species in Puget Sound, along with Elphidiella hannai and Eggerella advena, this fairly pollution-tolerant species is common worldwide in estuaries and shallow coastal seas.

Eggerella advena. This is one of the three most common species in Puget Sound (with Elphidiella hannai and Elphidium excavatum). It is highly pollution-tolerant, and is a pioneer colonizer of badly degraded waterways, particularly near sewage outlets. Large numbers of this species, in the absence of others, is generally not good news.

Trochammina pacifica and Trochammina hadai. These two species, which look quite similar, are noteworthy because T. hadai has often been mistakenly identified as T. pacifica. T. pacifica is a native species and T. hadai is an invader, possibly introduced from Japan when oysters were imported into Padilla Bay in the 1930s.

How do we collect and study forams?

The Department of Ecology personnel collect sediment samples from across Puget Sound.

The sediment is washed on board the ship to prepare it to go to the Burke Museum.

Once the sediment is at the Burke, the remaining mud must be removed. Here, volunteer Beverly Witte washes it through a fine sieve.

We use microscopes and small paint brushes to pick foraminifera out of the sediment and arrange them on small trays.

We take images of the forams and enhance images of the foraminifera on a laptop.

Students study the foraminifera and as part of their research and present their findings each spring.

What have we learned so far?

In our initial study of Puget Sound, we found 46 species of foraminifera. The species that appeared most often was a highly pollution-tolerant species called Eggerrella advena, and is most commonly found in Bellingham Bay, the South Sound, and near Bremerton.

The density of foraminifera (number of individuals per gram of sediment) varied dramatically throughout the Sound, as did the diversity, or number of species in each sample, and how they were distributed. Our research found that no one environmental factor, such as water depth, salinity, temperature, was responsible for the complex distribution of the foraminifera in Puget Sound. So, we've turned our attention to individual embayments to better understand what factors influence them.

Currently, we're looking at the northern part of Puget Sound, particularly Bellingham Bay and nearby Semiahmoo, Boundary and Birch Bays. Bellingham Bay has a history of pollution from industrial and agricultural activities in the surrounding area. We've found the highly pollution-tolerant Eggerella advena foraminifera dominating most of the area. But in some parts of the Bay, there are no foraminifera at all, which we speculate is due to a lack of oxygen, caused by the degradation of large amounts of organic matter.

In addition, we noted a deterioriation in the foraminiferal assemblages between 2006 and 2010. We studied chemicals in the sediments and looked for metals such as mercury, cadmium, arsenic, zinc and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in the water, but haven't pinpointed any single factor that could be causing this problem. Whatever the cause, it is clear that the foraminifera present indicate an unfriendly environment. Other studies are in the process of being published about the Hood Canal and Sinclair and Dyes Inlets near Bremerton.