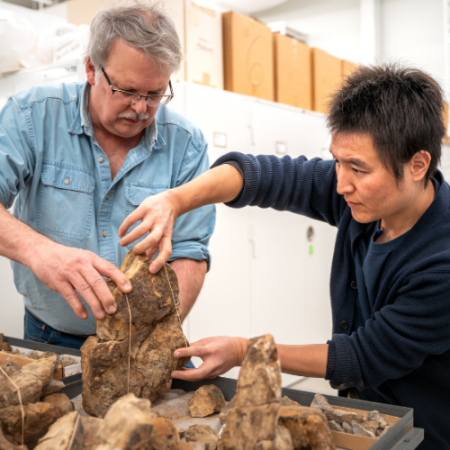

Dr. Robert Bossenecker, an adjunct professor at College of Charleston, visited the Burke Museum in January 2016 after being awarded the Burke’s Vertebrate Paleontology Collections Study Grant to study fossilized seal and sea lion (also known as pinniped) specimens.

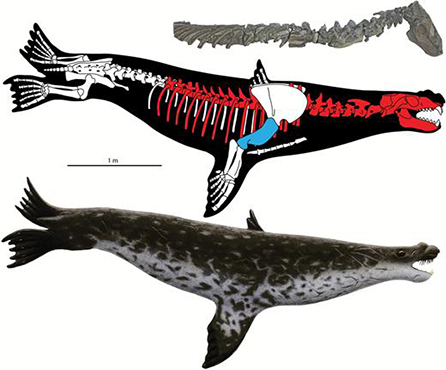

“All species of Allodesmus have a long, narrow skull and enormous eye sockets, thought to be an adaptation for deep diving,” said Robert. “They measured approximately three meters in length and weighed approximately 500-600 pounds.”

Diagram of Allodesmus demerei.

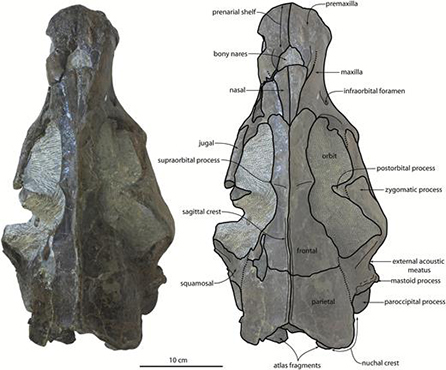

The skull of newly-discovered prehistoric seal species, Allodesmus demerei.

What can this newly-named species tell us about how this animal went extinct?

“Early walruses—which lacked tusks and were more seal and sea lion-like in anatomy—were becoming more diverse and achieving larger and larger body sizes,” said Robert. “So it appears that walruses may have outcompeted the desmatophocid seals and driven them to extinction.”

This new understanding of prehistoric pinnipeds provides important insights into the populations of today’s seals and sea lions.

“Currently we are experiencing the effects of what is known as a “sequential megafaunal collapse" in the North Pacific ecosystem with populations of small marine mammals—marine carnivores including seals, sea lions, and sea otters—decreasing during the late 20th century,” said Robert. But the reasons for those changes is still up for debate, making this new pinniped discovery even more vital.

“There is a lot that we don’t know about prey items in the middle to late Miocene,” said Robert. “Was there a major shift in the availability or type of fish and squid? The same time period is also the period in which modern kelp species diversified and presumably when kelp forests first became widespread; could this have affected prey availability?” We won’t know until more research is done.

“Much more work is needed,” said Robert. “Solid research on fossils is an important step to inform today’s conservation decisions.”

---

Read more about Dr. Robert Bossenecker’s previous visit to the Burke Museum, and learn more about the Vertebrate Paleontology Collections Grant.